Mediterranean Experience

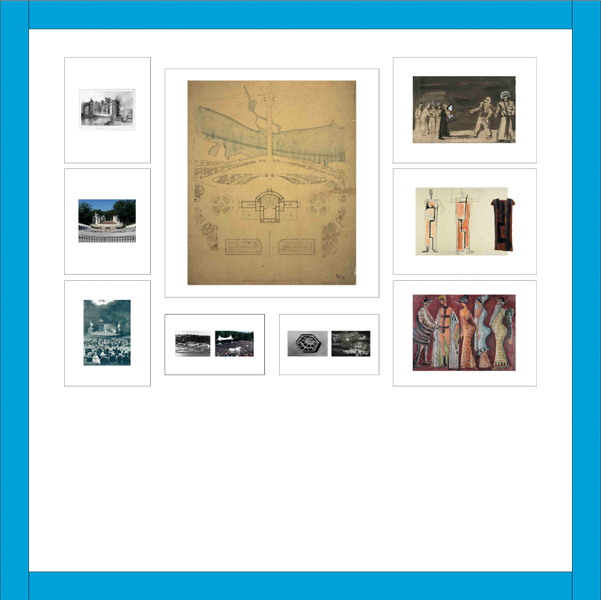

Distribution of known ancient Greek and Roman theatres

Distribution of known ancient Greek and Roman theatres European civilization started in ancient Greece. The Greeks were the first people in Europe to build cities, introduce an alphabet and mathematics, develop philosophy, natural sciences, literature, history, the Olympic Games, and democracy.

Since then, the Mediterranean influence has remained strong: Greek thinking shaped our sciences; Caesar and Augustus became models for almost every ruler in Europe, the Roman style an expression of power, and Roman law the foundation of our legislation; Christianity spread from Rome across the continent; the Pope dominated Medieval times; the Renaissance and the Baroque were developed in Italy and exported to all of Europe; the rediscovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum in the 18th century triggered the age of Classicism around 1800; and in the early 20th century, ancient Greece even influenced modern dance.

Around 500 BC, the ancient Greeks also invented theatre: tragedy and comedy and the permanent theatre building, and thus defined a cornerstone of European civilization.

N.N.

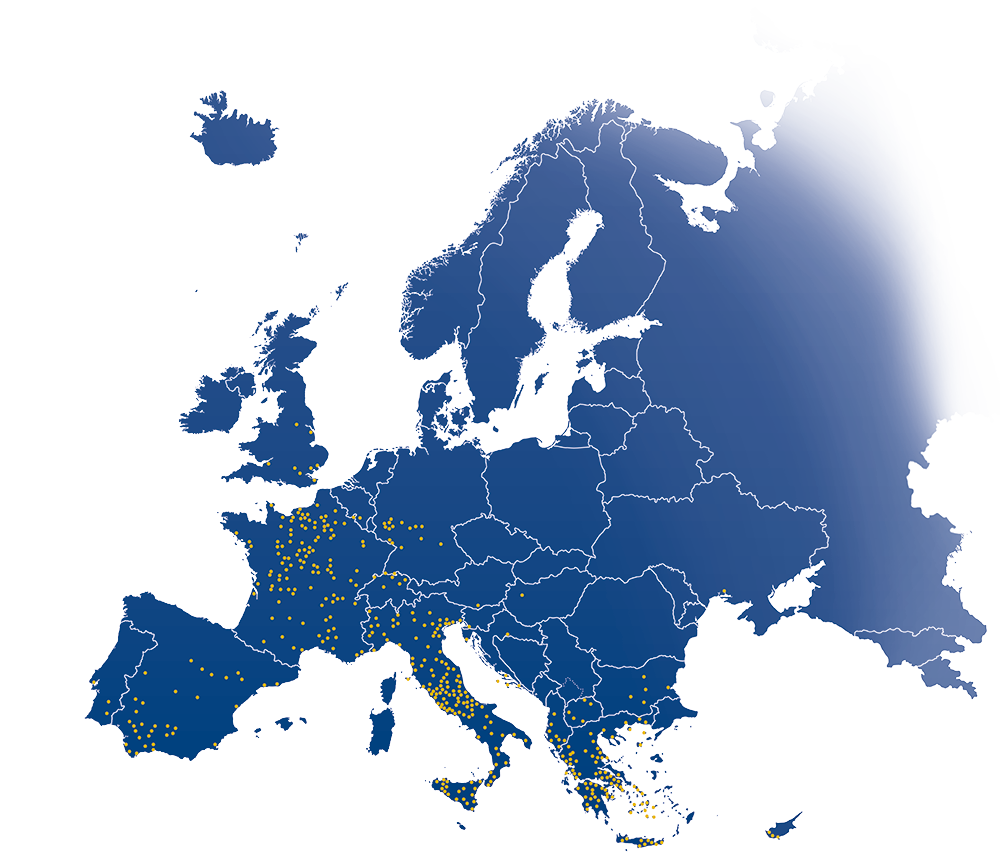

Model of the Theatre of Epidaurus (1998)

ca. 100 x 100 x 35 cm

Painted plaster and composite?

S.78-2008

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The theatre of Epidaurus was built around 340-330 BC as a part of the Asklepieion, a famous healing centre of Ancient Greece where Asclepius, God of medicines was revered. The theatre hosted music, song and drama competitions during the Asclepian games and is still in use today. Pausanias (ca. 110-180 AD) described the theatre as “especially worth seeing” (Pausanias II, 27. 5), stating that its architect Polyclitus was a master of symmetry and beauty. The attribution to Polyclitus is disputed today, however the theatre’s extraordinary acoustic, which allows the quietest sound uttered on the stage to be heard by spectators in the furthest row of seats, is not contested.

The theatre was built in two phases, first the lower tier for 8,000 spectators, and later the epitheatre (in mid 2d Century BC) accommodating 13,000 more. The stage area was originally built with a proscenium, a two storey stage and backstage area which have not survived.

Model of the Greek theatre in Epidaurus, built in the 4th century BC. The Greek theatre was quite simple but had brilliant acoustics. It consisted of rows of steps for the audience, built into the slope of a hill and forming an extended semicircle; a circular acting area in the centre;

and a long building that closed the semicircle and served as dressing room as well as a space to create special effects. Over the years, this long building grew in size and became an additional acting area, until the Romans confined acting exclusively to this part.

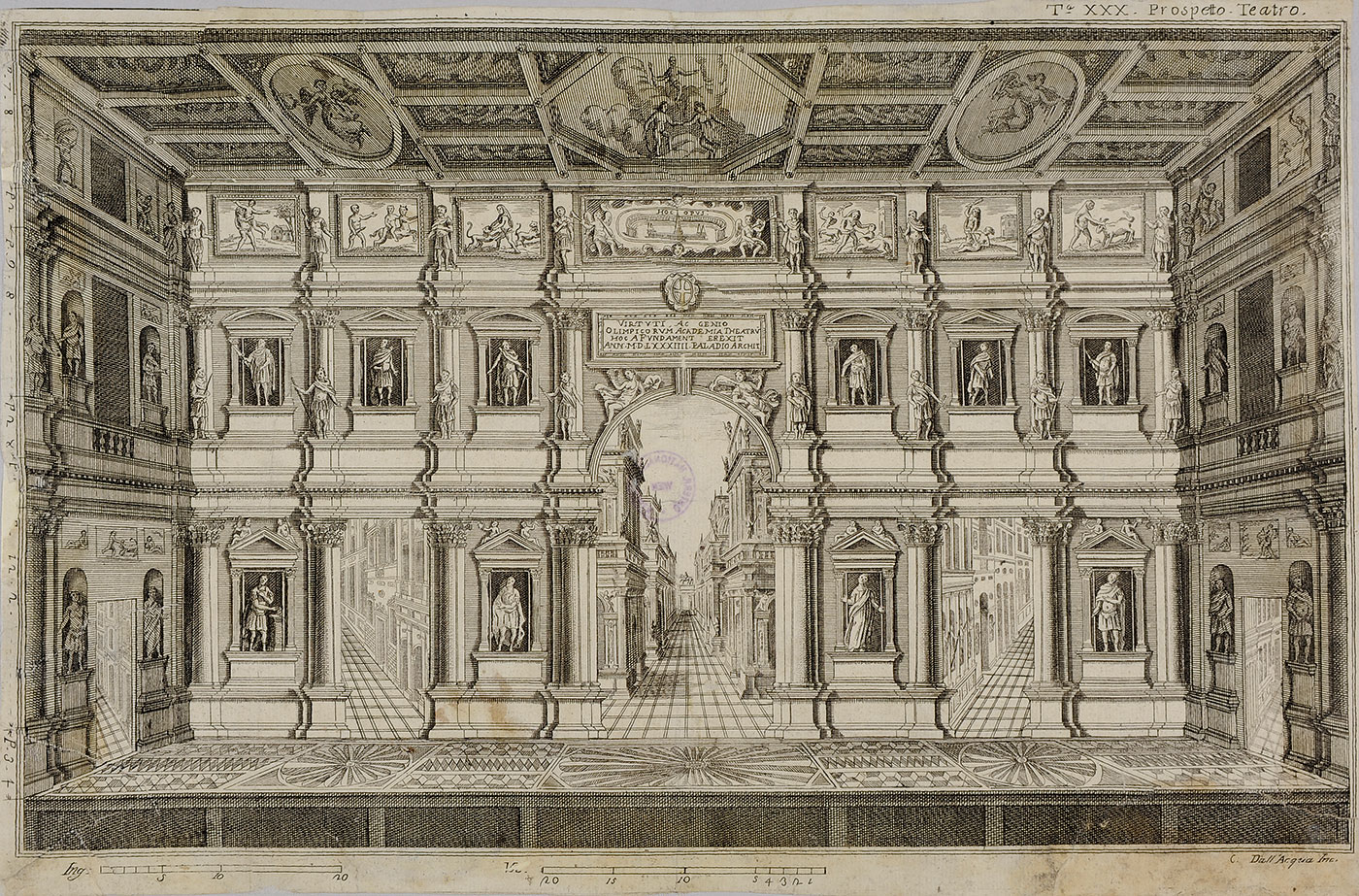

Andrea PALLADIO (1508-1580)

Vincenzo SCAMOZZI (1548-1616)

The stage of the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza (1585)

21 x 32 cm

Etching on paper

Etchings by Cristoforo dall’Acqua (c 1780)

GS_GBM6187

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza was constructed between 1580 and 1585. It was designed by the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio and finished by Vincenzo Scamozzi. The artists and literates of the Renaissance discovered the principles of the ancient Greek and Roman culture again and the Teatro Olimpico can be regarded as a revival of the architectural structure of Roman theatres. The permanent onstage scenery was created for the opening performance of the Greek tragedy “Oedipus the King” by Sophocles and the perspective views represent the streets of Thebes.

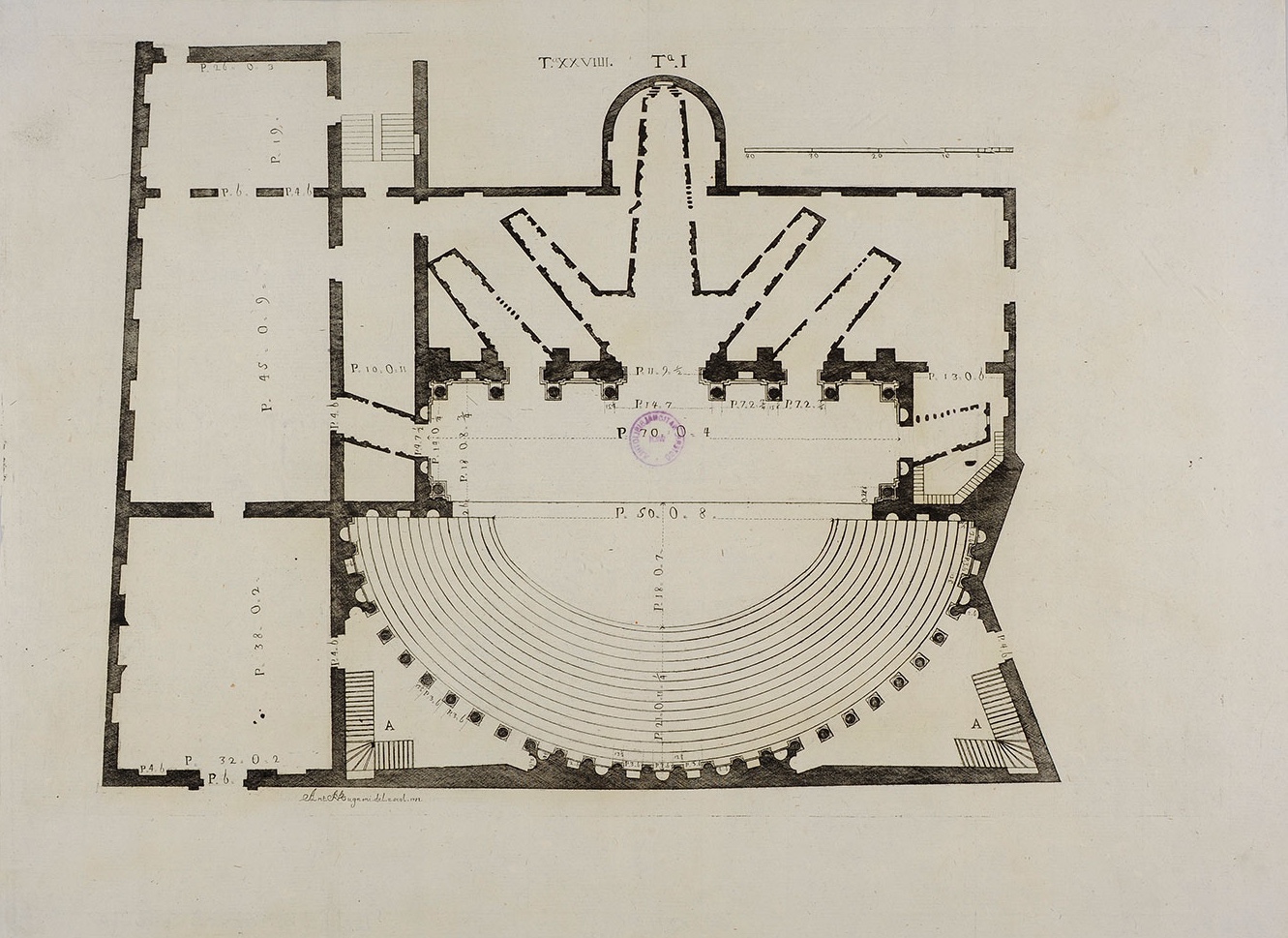

Andrea PALLADIO (1508-1580)

Vincenzo SCAMOZZI (1548-1616)

The ground plan of the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza (1585)

28.8 x 39 cm

Etching on paper

Etchings by Antonio Mugnoni (1788)

GS_GBU369

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza was constructed between 1580 and 1585. It was designed by the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio and finished by Vincenzo Scamozzi. The artists and literates of the Renaissance discovered the principles of the ancient Greek and Roman culture again and the Teatro Olimpico can be regarded as a revival of the architectural structure of Roman theatres. The permanent onstage scenery was created for the opening performance of the Greek tragedy “Oedipus the King” by Sophocles and the perspective views represent the streets of Thebes.

Andrea PALLADIO (1508-1580)

Vincenzo SCAMOZZI (1548-1616)

The auditorium of the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza (1585)

21 x 32 cm

Etching on paper

Etchings by Cristoforo dall’Acqua (c 1780)

GS_GBM6188

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza was constructed between 1580 and 1585. It was designed by the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio and finished by Vincenzo Scamozzi. The artists and literates of the Renaissance discovered the principles of the ancient Greek and Roman culture again and the Teatro Olimpico can be regarded as a revival of the architectural structure of Roman theatres. The permanent onstage scenery was created for the opening performance of the Greek tragedy “Oedipus the King” by Sophocles and the perspective views represent the streets of Thebes.

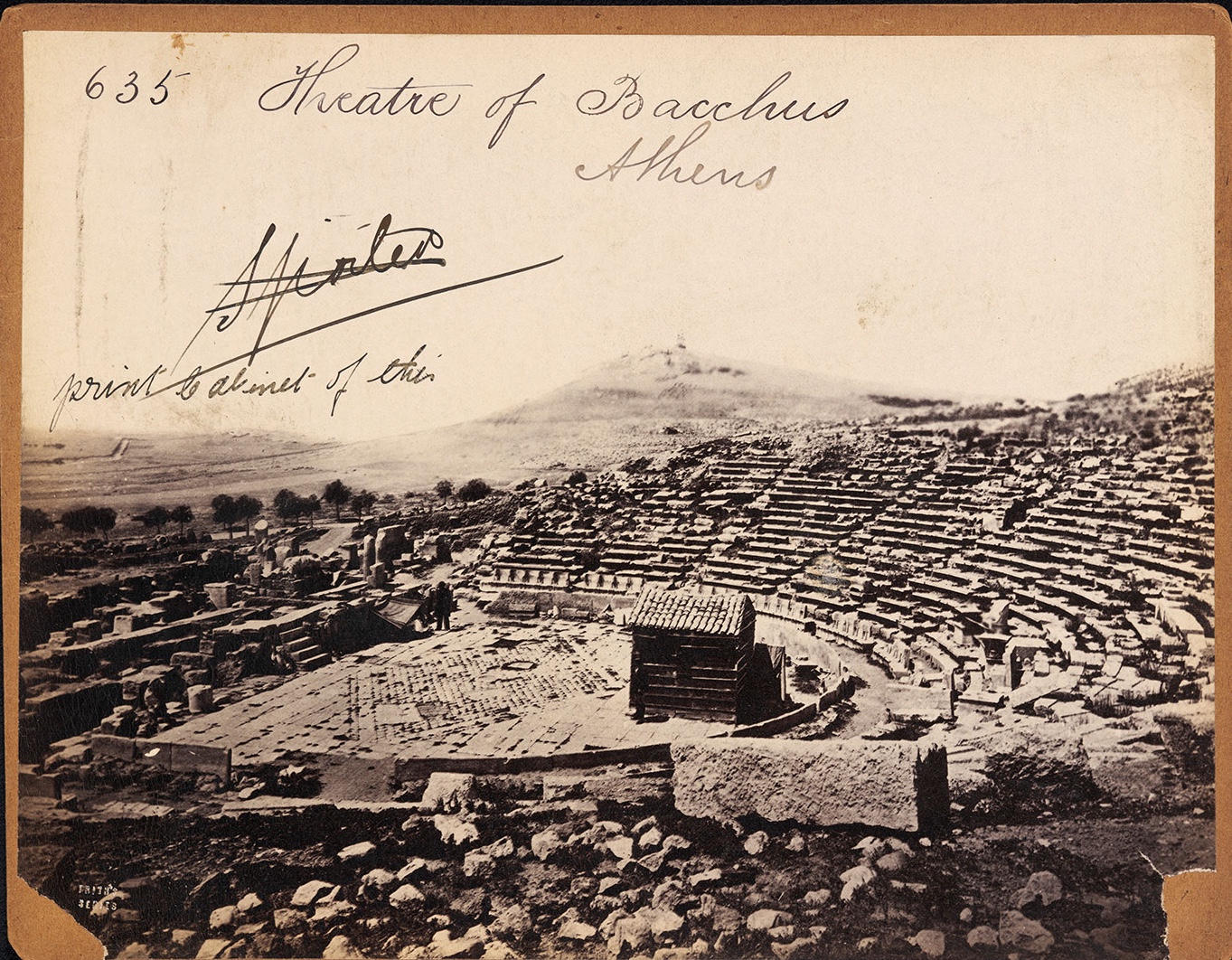

Francis FRITH (1822-1898)

Photograph of the Theatre of Bacchus /

Dionysus Theatre in Athens (1850s-70s)

16.1 x 20.3 cm

Whole-plate albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

E.208:172-1994

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Thanks to the development of photography, it became easier for art lovers of the 19th Century to see and learn more about remote and iconic places. The theatre of Bacchus is one of the oldest Greek theatres, dating from around 5th Century BC and is sometimes considered the birthplace of classical antique theatre.

This photograph is part of the Francis Frith Archive at the V&A – Frith developed his business in the 1860s, becoming the first photographic firm in England of far-reaching reputation. He recognised that tourists and armchair travellers were hungry for topographic views of ancient civilisations, and he employed several photographers to realise the “Universal Series” – from which this picture is one example. Such a choice of photographs would enable the Victorians to ‘compare’ their civilisation to the grand civilisations of the past, and contrast their own achievements in Industry and Technology. This photograph demonstrates the perennial interest in classical models of theatre construction: the semi-circular seating area around the stage is a model we still use today.

Christian Schieckel

Model of the Dionysus Theatre in Athens (around 1980)

37.5 x 200.4 x 144.2 cm

Coloured wood

Photo by Klaus Broszat

F386

German Theatre Museum; Munich

A model of the famous theatre in Athens, where the “Dionysia” took place 5th to 4th century BC.

Jean-Eugène-Auguste ATGET (1857-1927)

Photograph of an antique mask sculpture (1923-24)

16.8 x 21.5 cm

Whole-plate albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Printed by Berenice ABBOTT

CIRC.414-1974

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In the 19th Century, interest in ancient Greek theatre was as widespread as in the 16th Century. Here Eugène Atget, French photographer famous for his photographs recording the streets and buildings of old Paris, photographed an antique sculpture in an unknown location. Atget turned to photography recognising that contemporary artists needed to document their work. His own work would have remained unknown if the photographer Berenice Abbott, who admired him, had not published and promoted it.

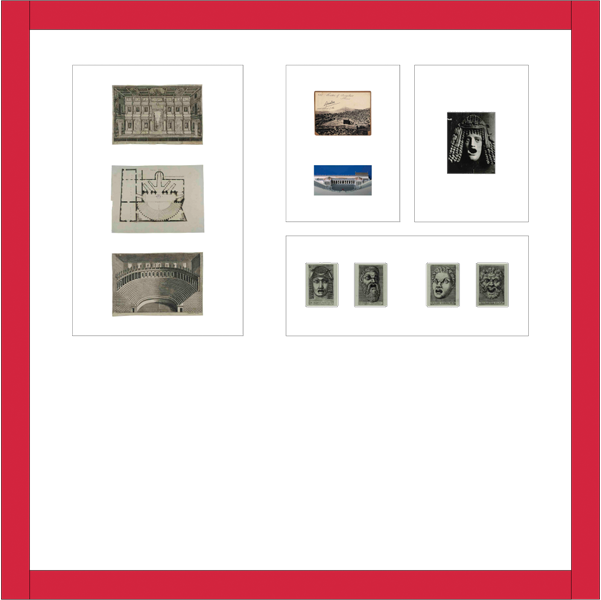

N.N.

and Antonio LAFRERY (publisher, 1512-1577)

Etching of a Roman actor’s mask (1573)

12.9 x 8.1 cm

Etching

E.2045-1899

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

During the Renaissance, etchings and engravings of Greek and Roman works of art were circulated amongst artists searching for sources of inspiration in classicism. These etching show several actors’ masks, with notes of where the original sculptures could be found on the Grand Tour route in Italy.

In antique theatre, in the same way as in Japanese No theatre, actors would wear masks to emphasize the dramatic or comic aspects of their characters. This young soldier (possibly) could have been found In Hortis Vaticanis, namely the gardens of the Vatican.

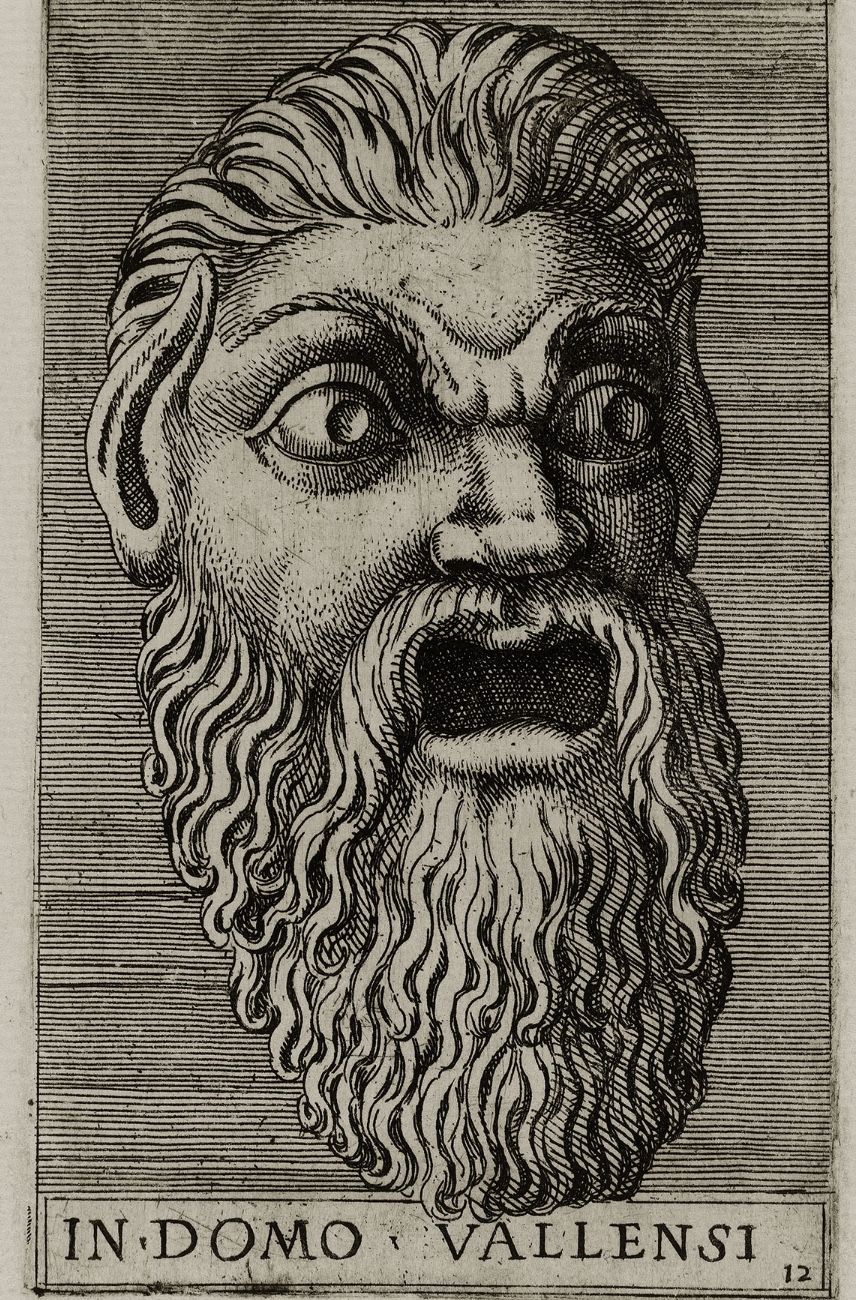

N.N.

and Antonio LAFRERY (publisher, 1512-1577)

Etching of a Roman actor’s mask (1573)

12.9 x 8.1 cm

Etching

E.2050-1899

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

During the Renaissance, etchings and engravings of Greek and Roman works of art were circulated amongst artists searching for sources of inspiration in classicism. These etching show several actors’ masks, with notes of where the original sculptures could be found on the Grand Tour route in Italy.

In antique theatre, in the same way as in Japanese No theatre, actors would wear masks to emphasize the dramatic or comic aspects of their characters. This mask of an old man could be found at the time of publishing In Domo Vallensi, in the house of V.

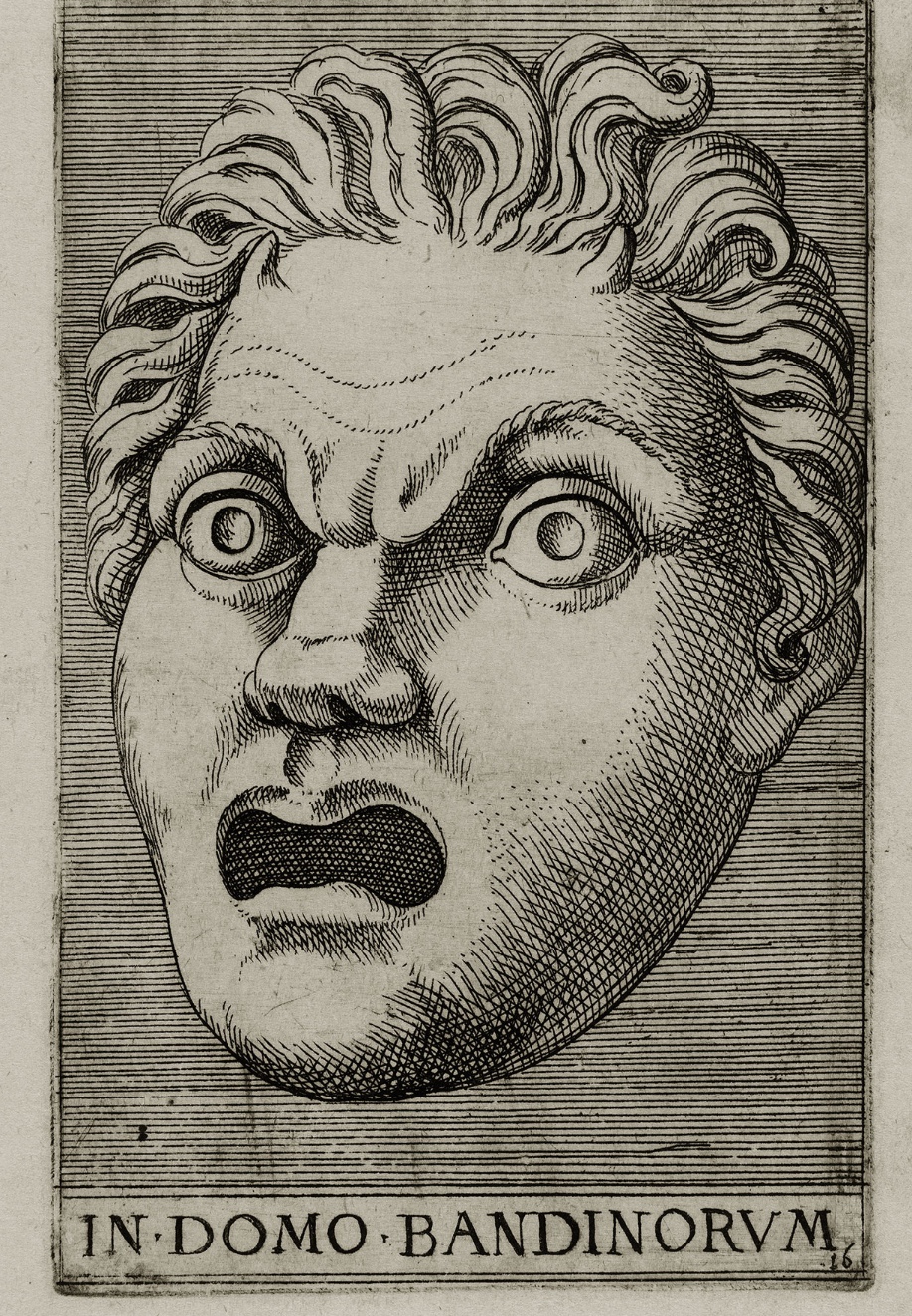

N.N.

and Antonio LAFRERY (publisher, 1512-1577)

Etching of a Roman actor’s mask (1573)

12.9 x 8.1 cm

Etching

E.2054-1899

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

During the Renaissance, etchings and engravings of Greek and Roman works of art were circulated amongst artists searching for sources of inspiration in classicism. These etching show several actors’ masks, with notes of where the original sculptures could be found on the Grand Tour route in Italy.

In antique theatre, in the same way as in Japanese No theatre, actors would wear masks to emphasize the dramatic or comic aspects of their characters. This mask could have been found In Domo Bandinorum, i.e. in the house of B.

N.N.

and Antonio LAFRERY (publisher, 1512-1577)

Etching of a Roman actor’s mask (1573)

12.9 x 8.1 cm

Etching

E.2053-1899

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

During the Renaissance, etchings and engravings of Greek and Roman works of art were circulated amongst artists searching for sources of inspiration in classicism. These etching show several actors’ masks, with notes of where the original sculptures could be found on the Grand Tour route in Italy.

In antique theatre, in the same way as in Japanese No theatre, actors would wear masks to emphasize the dramatic or comic aspects of their characters. This satyr mask could be found Ad Fontem Iulium, which means on the “Fountain of July” or possibly “Julius’ fountain” in reference of Pope Julius II.

The Greek theatre was transformed by the Romans into a free standing building, closed off from the city by a huge stage wall, embellished with columns and statues of the emperors. This Roman version was revived in the Renaissance, e.g. in the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza, Italy, mirrored here in etchings from the late 18th century, the age of Classicism.

What we see of our past today was dug out, cleaned, restored, and re-erected in the 18th, 19th and 20th century. Even at the Dionysus Theatre in Athens, the first theatre building in Europe (ca. 500 BC, stone version 340 BC), the starting point was assorted marble pieces, as documented in the photo from the 1870s AD.

Below: a reconstruction of the simple Greek stage house.

Our ideas of classical staging come from painted walls and vases, marble works and stone masks used as decoration, since no theatre masks or costumes have survived. In the Renaissance, this evidence was published in print, as in Antonio Lafrery’s edition from 1573. Centuries later, Eugène Atget took a photo in Paris of a neo-Roman masque, a fashionable decorative element around 1900.

Jean-Léon GÉRÔME (1824-1904)

The comedians

Photogravure by Goupil & Cie (1865)

Original size of the painting 60 x 46 cm, as reproduced here

Private collection

The French painter Gérôme exhibited this painting, entitled “The Mask Merchants”, in 1863 and sold it to the Goupil Gallery in 1864. Goupil, who became Gérôme’s father-in-law, had discovered how to make a lot of money by reproducing works of art as photogravures and postcards, naturally in black and white or sepia. Between 1865 and 1885, he sold photos of this painting, now called “The Comedians”, in five different formats, ranging from visiting card to picture book. The oil painting vanished after 1904. It only survives in the Goupil photographs and in a small oil sketch at Compiègne Palace.

The second half of the 19th century saw a revival of the styles of all ages, among them Greek and Roman antiquity. They appeared in serious history paintings or got a comic twist, as in this painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, “The Comedians”, 1863.

Sharing the fate of many artefacts from antiquity, the original oil painting has disappeared and survives only in this 19th century photograph…

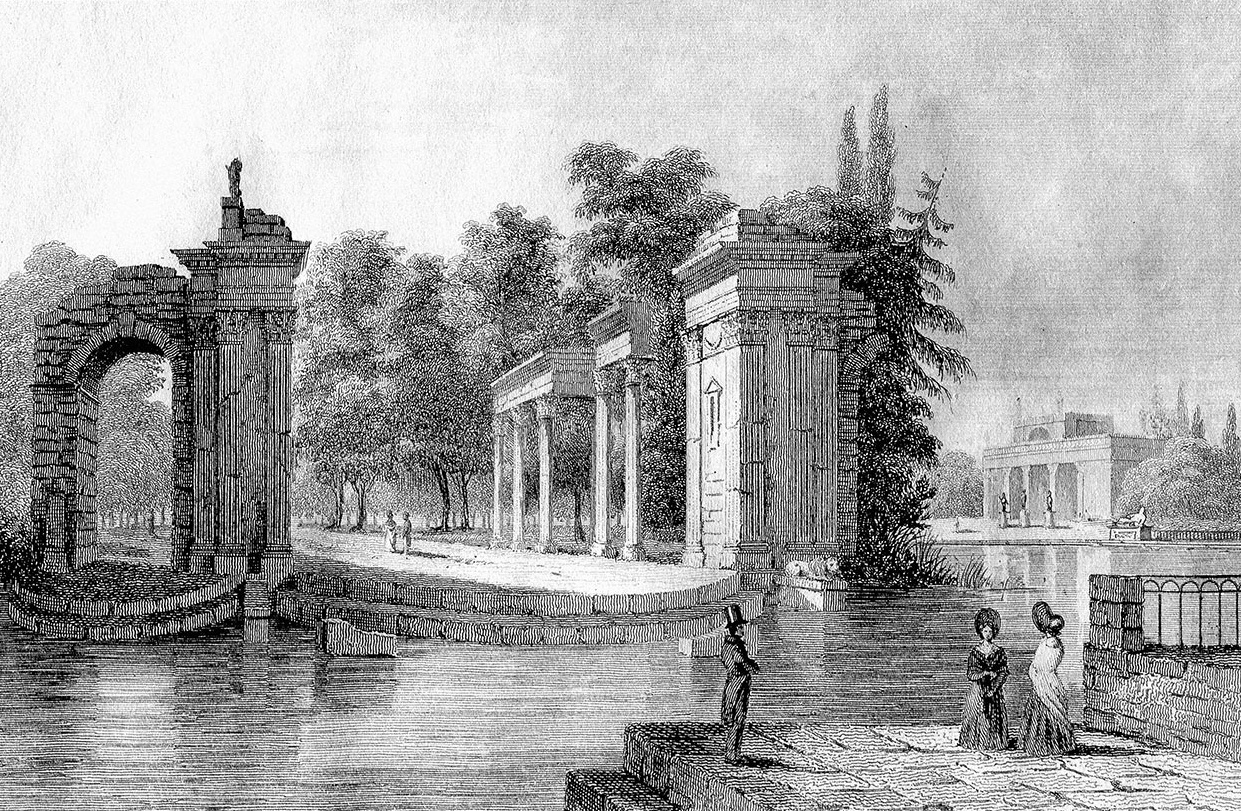

Augustin François LEMAÎTRE (1797-1870)

The Theatre on the Island in Royal Łazienki Park in Warsaw

12.6 x 18.2 cm

Print on paper

MT/III/109

Theatre Museum, Warsaw

This open-air theatre dates from 1791. It features a semicircular auditorium on the park side and a stage on the island, decorated with antique columns. In front of the stage, there is a pit for the orchestra. It is at level with the water in the canal that separates auditorium and stage – a unique feature of this theatre, predating all opera on the lake venues of today by 200 years.

Monika BOCHEŃSKA

The Theatre on the Island in Łazienki Park today

Photograph (2014)

© Monika Bocheńska

This open-air theatre dates from 1791. It features a semicircular auditorium on the park side and a stage on the island, decorated with antique columns. In front of the stage, there is a pit for the orchestra. It is at level with the water in the canal that separates auditorium and stage – a unique feature of this theatre, predating all opera on the lake venues of today by 200 years.

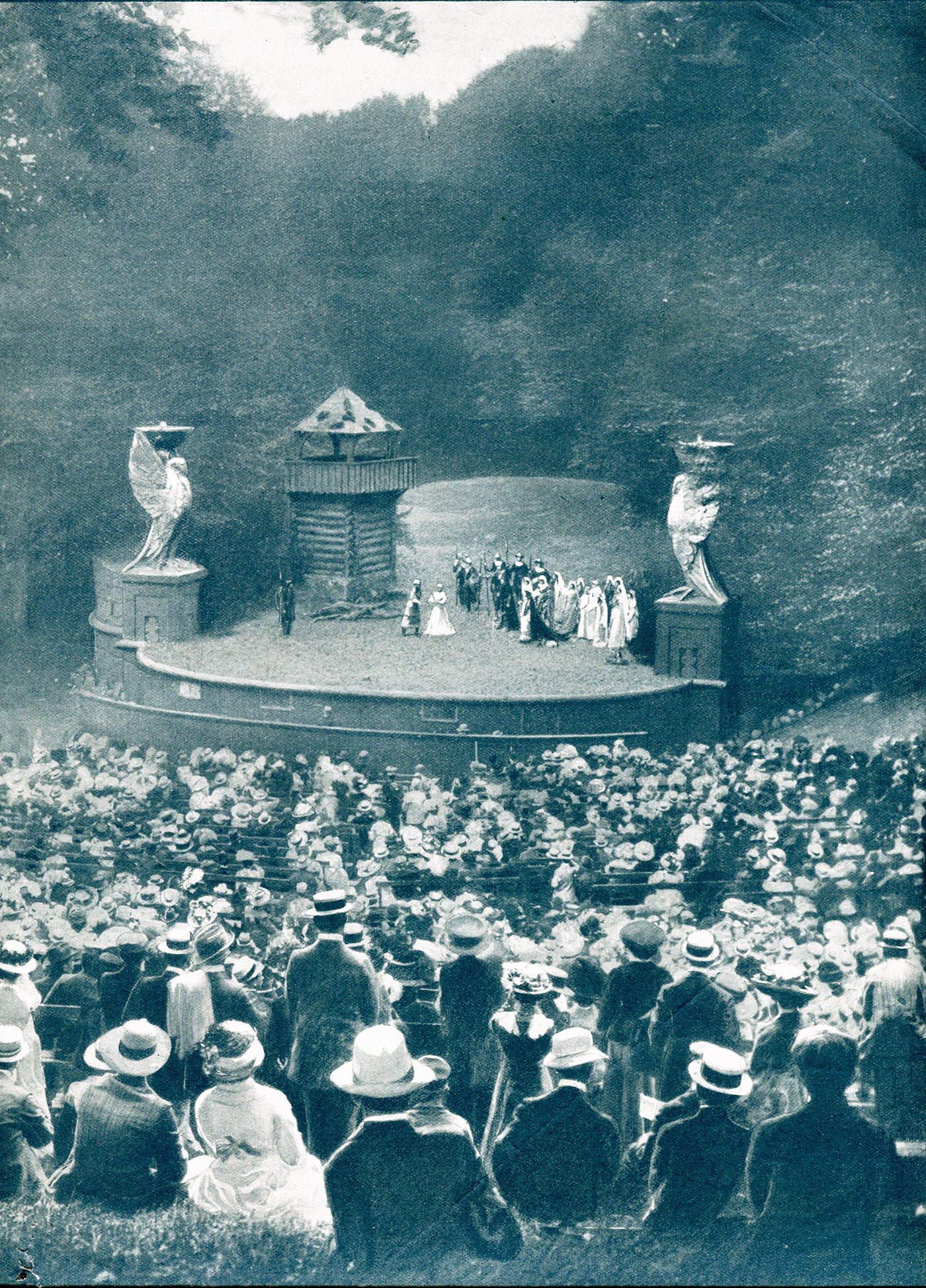

“Holding the mirror up to nature. The new open-air theatre for Copenhagen”

Press cutting from 1900

24 x 33.5 cm

Print on paper

Theatre Museum, Warsaw

In 1900 an open-air theatre was inaugurated in Deer Park, Copenhagen, with “Midsummer Night's Dream“.

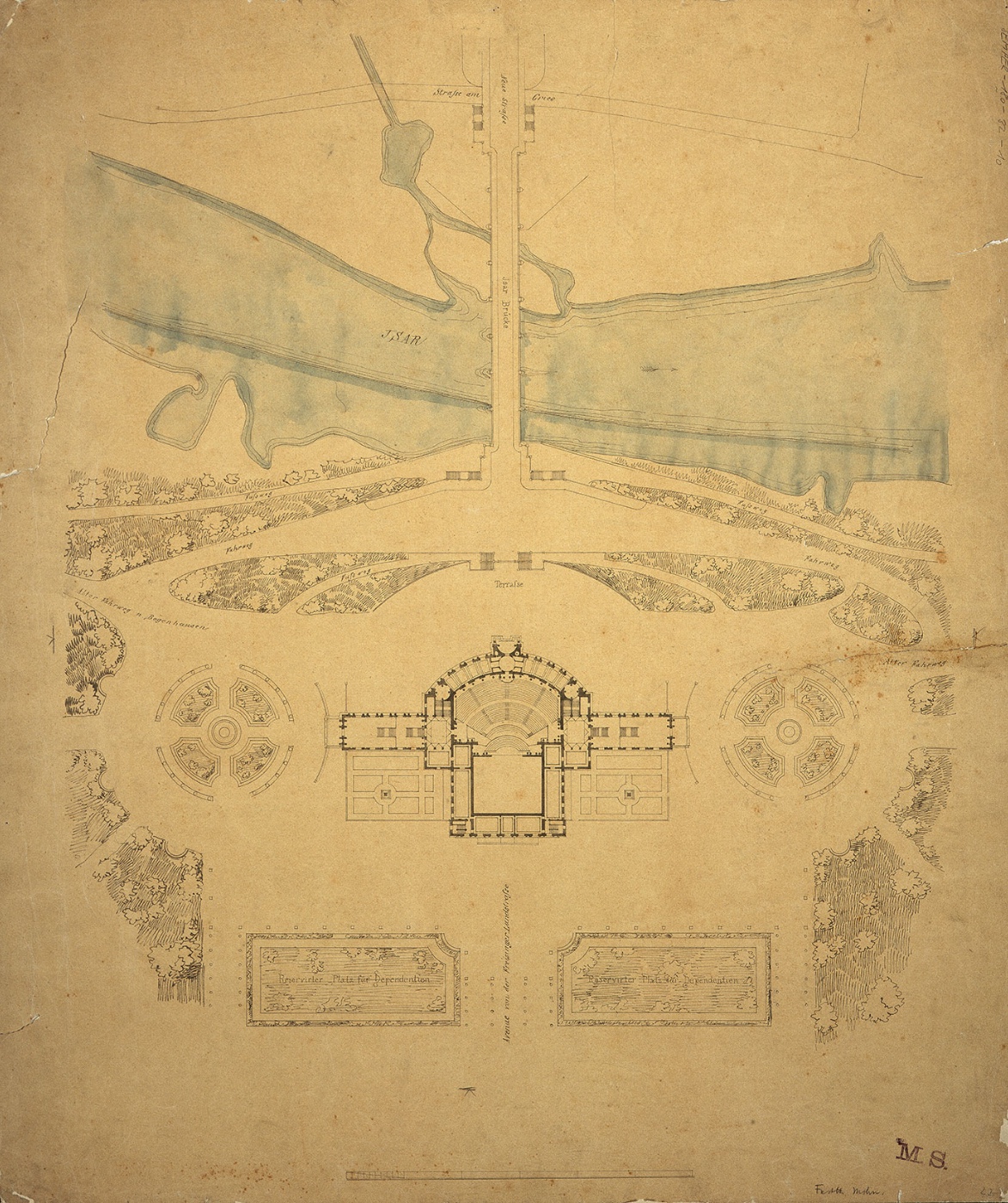

Gottfried Semper (1803-1879)

Topographic plan of the Festspielhaus Munich (1866)

61.1 x 71.4 cm

Pencil, watercolour on paper

F1190

German Theatre Museum, Munich

The earliest example of the renaissance of the ancient auditorium of the Greek and Roman theatres.

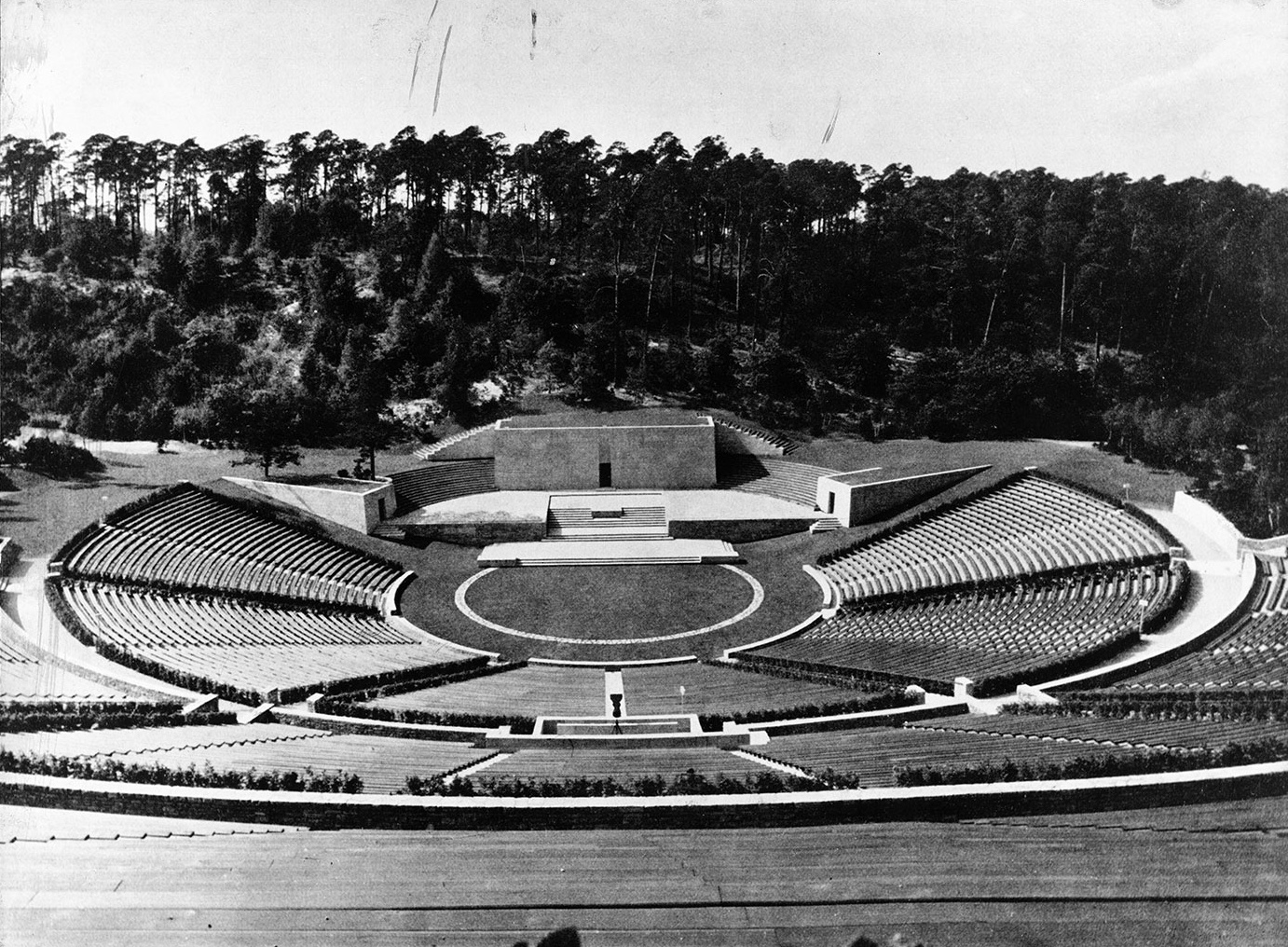

Werner MARCH (1894-1976)

Dietrich Eckart Open-air Theatre, Berlin (1936)

Photo

Inv.Nr. F 5327

Courtesy of Architekturmuseum TU Berlin

From 1933 onward, the Nazi’s started a huge construction programme for open-air theatres all over Germany. In these theatres they wanted to present a Nordic kind of play, the “Thingspiel”. As no such plays existed, a group of authors was convened by the Ministry of Propaganda to create them. 400 of the open-air theatres, called “Thingspielstätten”, were to be built, but only some 60 materialized by 1936, when the Ministry found that other forms of propaganda were more efficient and dropped the idea. Although the theatre was intended to be very Nordic, the architect had studied Greek and Roman theatres in Italy in preparation. The theatre is still used today, now called “Waldbühne”.

Lutz WIEHLE

Waldbühne Berlin

Photo (2008)

Courtesy of Lutz Wiehle

www.flickr.com/photos/lwiehle/2698697956

The “Waldbühne”, today mainly used for concerts, was created as part of the Olympic Games 1936 grounds and as part of a huge construction programme for open-air theatres in all of Germany. In these theatres, the Nazis wanted to present a Nordic kind of play, the “Thingspiel”. As no such plays existed, a group of authors was convened by the Ministry of Propaganda to create them. 400 of the open-air theatres, called “Thingspielstätten”, were to be built, but only some 60 materialized by the end of 1936, when the Ministry found that other forms of propaganda were more efficient and dropped the idea. Although the theatre was intended to be very Nordic, the architect had studied Greek and Roman theatres in Italy in preparation.

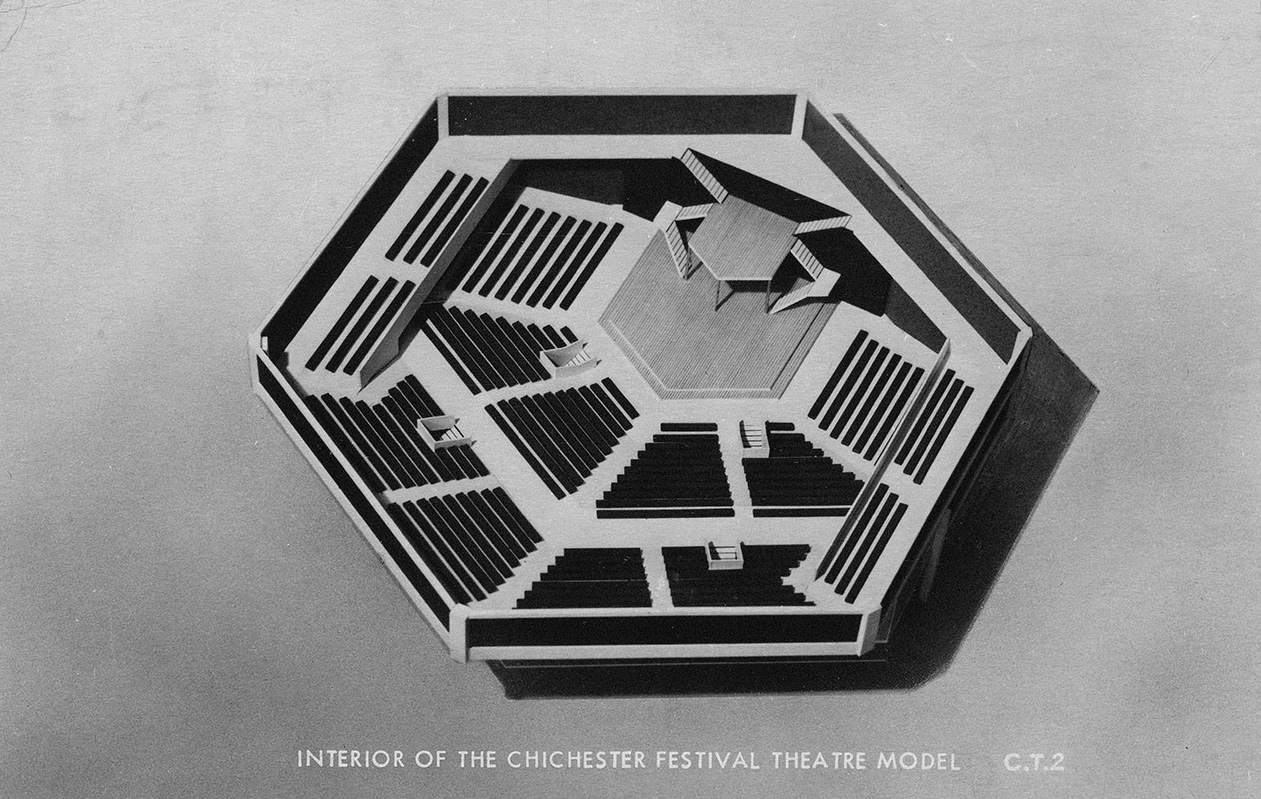

N.N.

Model of the interior of the Chichester Festival Theatre (1961)

13.9 x 8.9 cm

Postcard

Theatre and Performance Archive

© V&A, with permission of Chichester Festival Theatre

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Chichester Festival Theatre was founded in 1962 by Leslie Evershed-Martin (former city Mayor) and Laurence Olivier (Artistic Director 1962-65), as a seasonal summer theatre, inspired by the Tyrone Guthrie Theatre Festival in Stratford, Ontario (CA). The building was designed by the British architect Philip Powell and the American John Hidalgo Moya, who arranged the auditorium around the stage, mixing models from ancient Greece and Elizabethan theatre. This thrust stage enabled the actors to be in closer proximity to the audience and create more intimacy between spectators and performers.

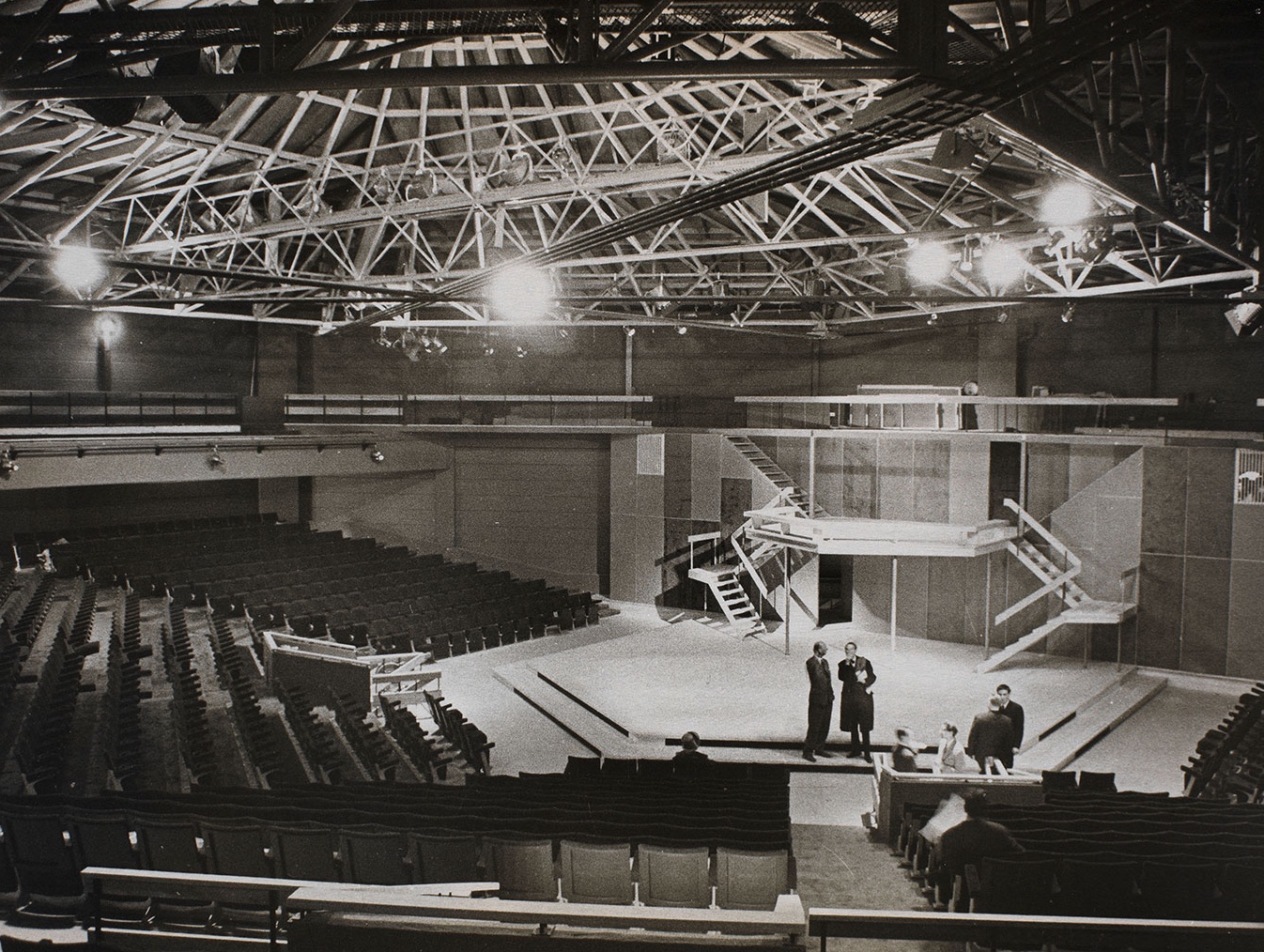

N.N.

Press preview of Chichester Festival Theatre (May 1962)

23.8 x 17.8 cm

Photograph

Theatre and Performance Archive

© V&A, with permission of Chichester Festival Theatre

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Chichester Festival Theatre was founded in 1962 by Leslie Evershed-Martin (former city Mayor) and Laurence Olivier (Artistic Director 1962-65), as a seasonal summer theatre, inspired by the Tyrone Guthrie Theatre Festival in Stratford, Ontario (CA). The building was designed by the British architect Philip Powell and the American John Hidalgo Moya, who arranged the auditorium around the stage, mixing models from ancient Greece and Elizabethan theatre. This thrust stage enabled the actors to be in closer proximity to the audience and create more intimacy between spectators and performers.

Caspar NEHER (1897-1962)

Draft stage design for “The Antigone of Sophocles” by Bertolt Brecht (1948)

29 x 44 cm

Ink wash, opaque white

IV 7568, F 2811

German Theatre Museum

Permanent loan from Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung

Scene: Antigone in chains in front of Creon

This production at the Stadttheater Chur, premiered on February 15th, 1948 was the first theatre work by Brecht returning to Europe after his exile, and the first meeting and collaboration with his friend Caspar Neher after the Second World War. The theme of burying one’s own brother, husband or son was very topical.

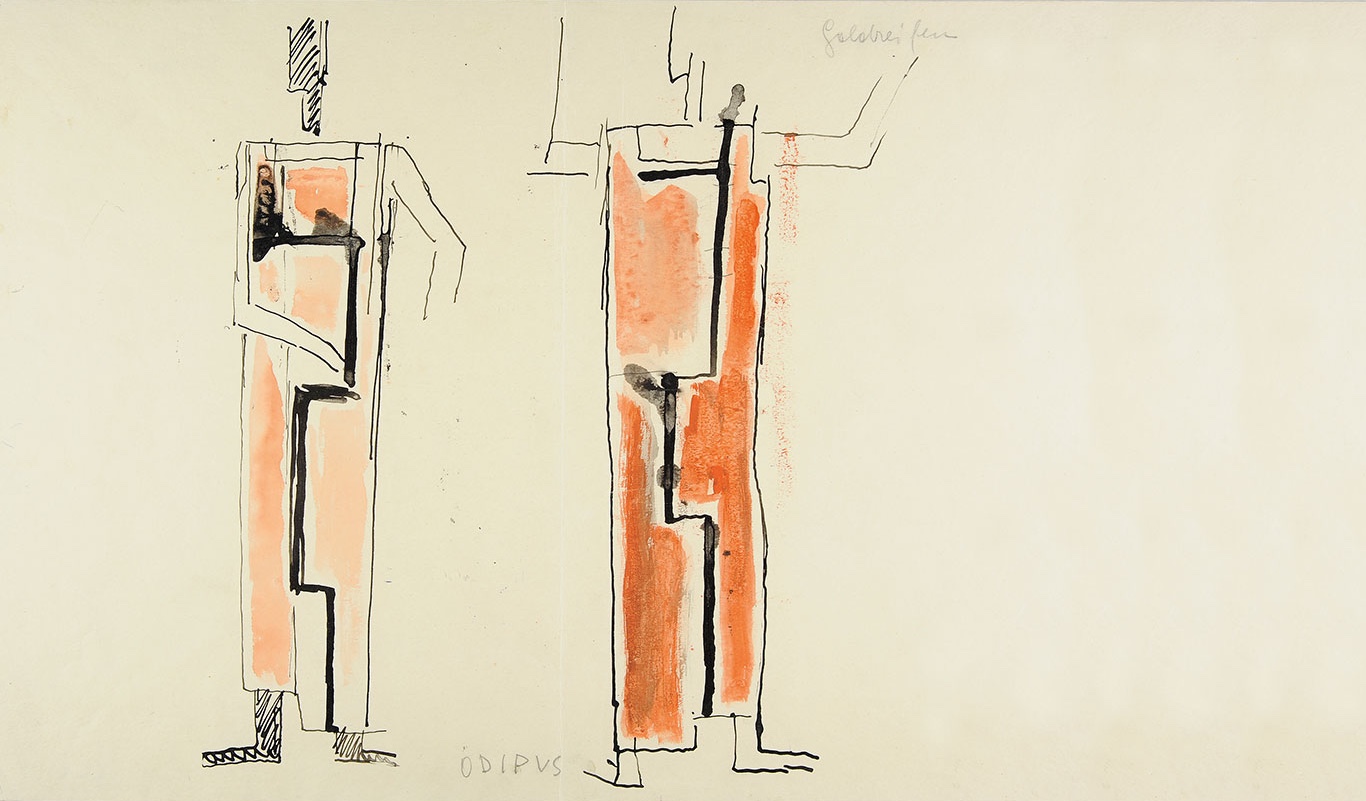

Fritz WOTRUBA (1907-1975)

Costume design for “Oedipus the King” (1960)

29.8 x 41.9 cm

Ink, watercoulour and guache on paper

HZ_HU21292

Theatre Museum, Vienna

Fritz WOTRUBA (1907-1975) created the stage and costume design for Gustav Rudolf Sellners production of “Oedipus the King” by Sophocles which premiered at the Burgtheater in Vienna on April 5th. The costume design represents a modern interpretation of the ancient character of Oedipus by creating a costume reflecting the style of the late 1950ies and early 1960ies. It also reminds the spectator of architectural elements like columns and stone ruins associated with the Greek antiquity. The costume itself is made of unconventional materials like wool, cotton and linen canvas and conveys a feeling of stiffness, rigidity and heaviness that of course had a specific impact on acting. The costume was worn by the actor Erich Schellow at the end of the tragedy when Oedipus had already blinded himself.

Fritz WOTRUBA (1907-1975)

Costume design for “Oedipus the King” (1960)

29.8 x 41.9 cm

Ink, watercoulour and guache on paper

HZ_HU21292

Theatre Museum, Vienna

Fritz WOTRUBA (1907-1975) created the stage and costume design for Gustav Rudolf Sellners production of “Oedipus the King” by Sophocles which premiered at the Burgtheater in Vienna on April 5th. The costume design represents a modern interpretation of the ancient character of Oedipus by creating a costume reflecting the style of the late 1950ies and early 1960ies. It also reminds the spectator of architectural elements like columns and stone ruins associated with the Greek antiquity. The costume itself is made of unconventional materials like wool, cotton and linen canvas and conveys a feeling of stiffness, rigidity and heaviness that of course had a specific impact on acting. The costume was worn by the actor Erich Schellow at the end of the tragedy when Oedipus had already blinded himself.

Alenka BARTL (1930)

Costume design sketch for “Lysistrata” by Aristophanes (1975)

77 x 57 cm

Paper sketch

Private collection

Aristophanes, “Lysistrata”, directed by Miran Herzog, Slovenian National Theatre Drama Ljubljana, premiere 26 December 1975

The Greek theatre model has been used naturally for open-air theatres since they became fashionable again in the 18th century, e.g. in Warsaw (above) and Copenhagen (below). In Germany, it even influenced Nazi propaganda theatres of the 1930s (bottom). With interiors, Greek theatres inspired plans for a festival theatre in Munich by Semper in 1866 (plan), and the actual festival theatre in Chichester by Powell & Moya in 1962 (below right).

Besides the remains of theatre buildings, plays from antiquity have come down to us and are still being produced today, after 2500 years. A challenge is to find modern versions of classical costumes, like Caspar Neher created for “Antigone” by Sophocles/Brecht, 1948 (top); Fritz Wotruba for “Oedipus Rex” by Sophocles, 1960 (centre); and Alenka Bartl for the comedy “Lysistrata” by Aristophanes, 1975 (bottom).