Changing Society - Changing Building

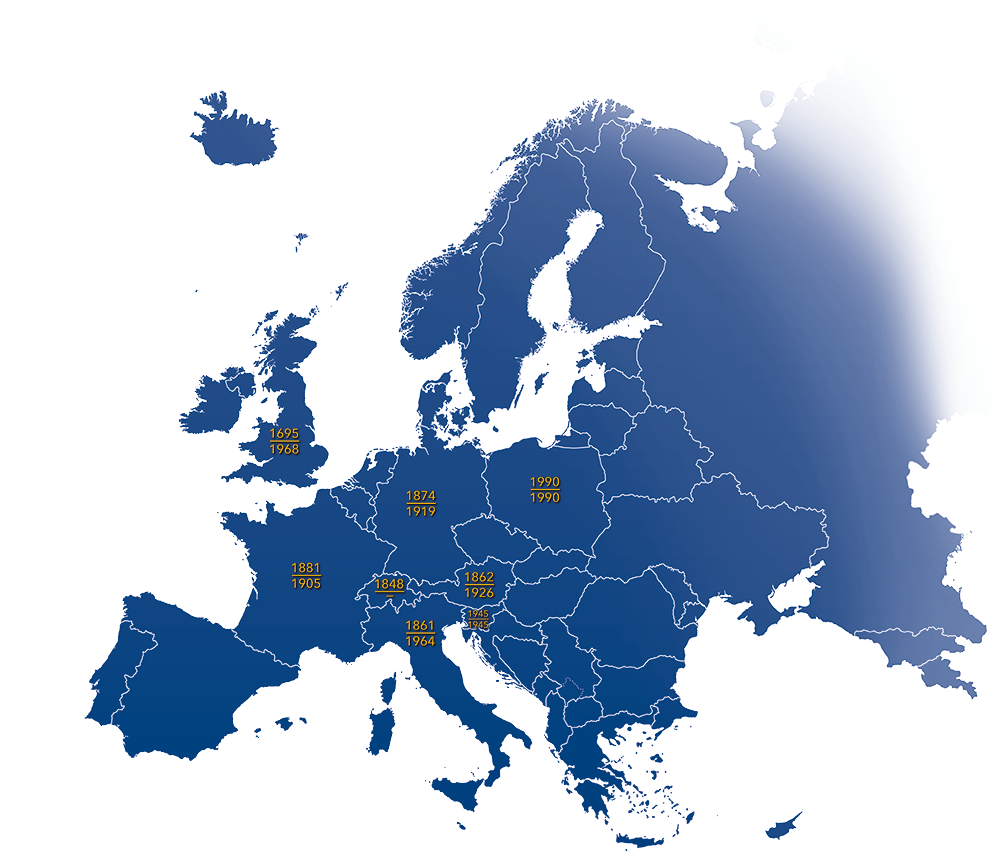

Definitive introduction of freedom of the press / abolition of theatre censorship in selected countries

Money is power. And power means money. This has been so since the invention of the first currency. And those who have money built theatres, at least in Europe. Hence theatre buildings are also an expression of power – or mainly of money, as in commercial theatres.

Looking at a theatre building, it is therefore useful to ask: who built this theatre and why? How is this intention expressed in the architecture? What do the paintings on the ceilings and other decorative elements tell us? Who used the building? How were the audience originally distributed in the auditorium and to what effect?

As societies change, theatres change, mirroring the changes in society: from aristocratic to bourgeois society, from the rise of the working class to the uniform society under a dictator, from a new idea of an open society in the second half of the 20th century to… All this is reflected in the architecture of the theatres: in the way the existing buildings have been altered, as well as in the new buildings of each era.

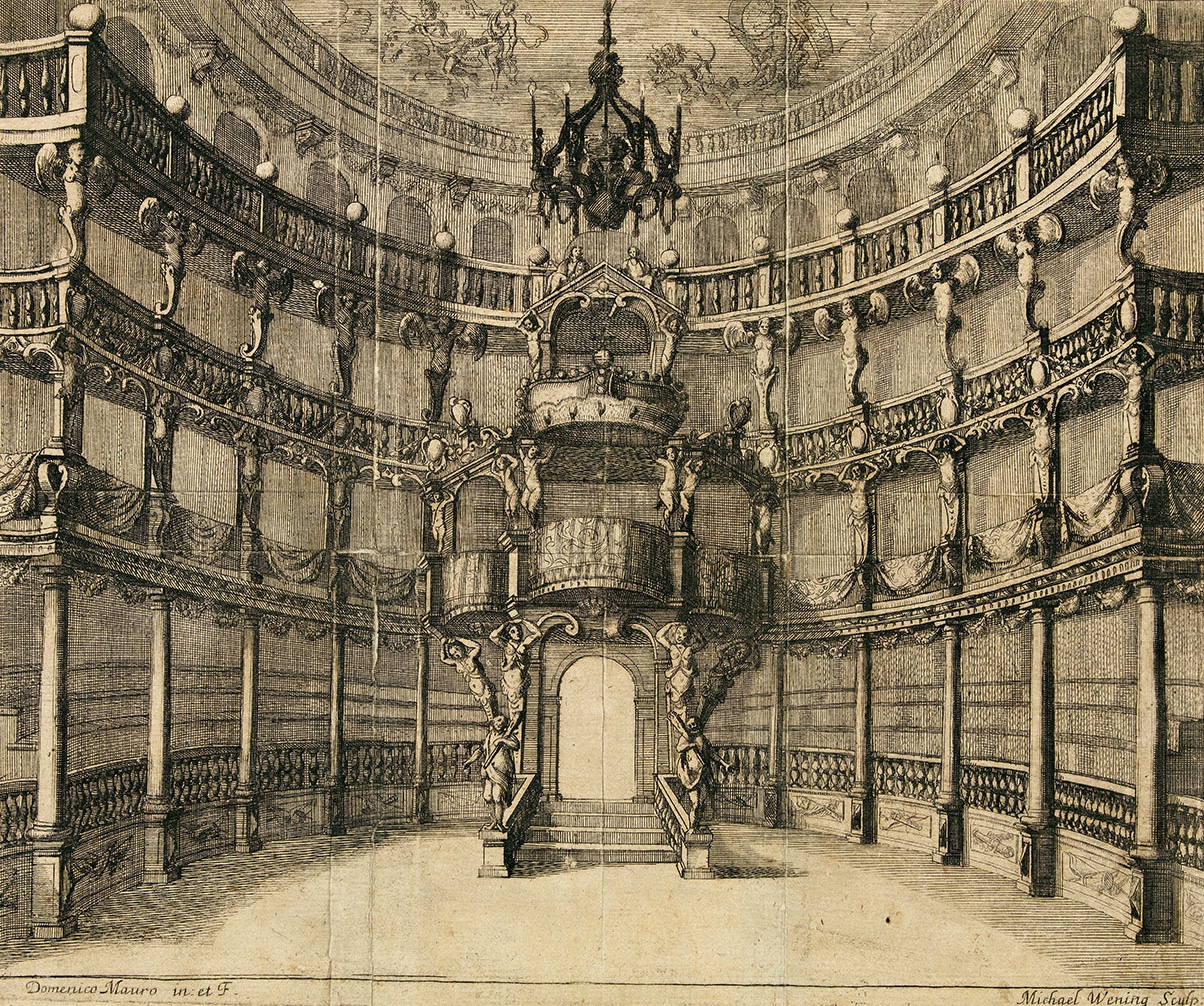

Domenico MAURO (f.R. 1685 - l.R. 1693)

Salvator Theatre München (around 1685)

27 x 31 cm

Engraving by Michael Wening

after a drawing by Domenico Mauro,

separated from the libretto of Servio Tullio Steffani, also in this collection

I 11567/1, F 911

German Theatre Museum

Interior of the Salvator Theatre, the oldest independent architecture of an opera house in Germany.

An early German example for the structure of balconies and boxes with the best view and the most beautiful and representative ambience for the sovereign of the aristocratic society.

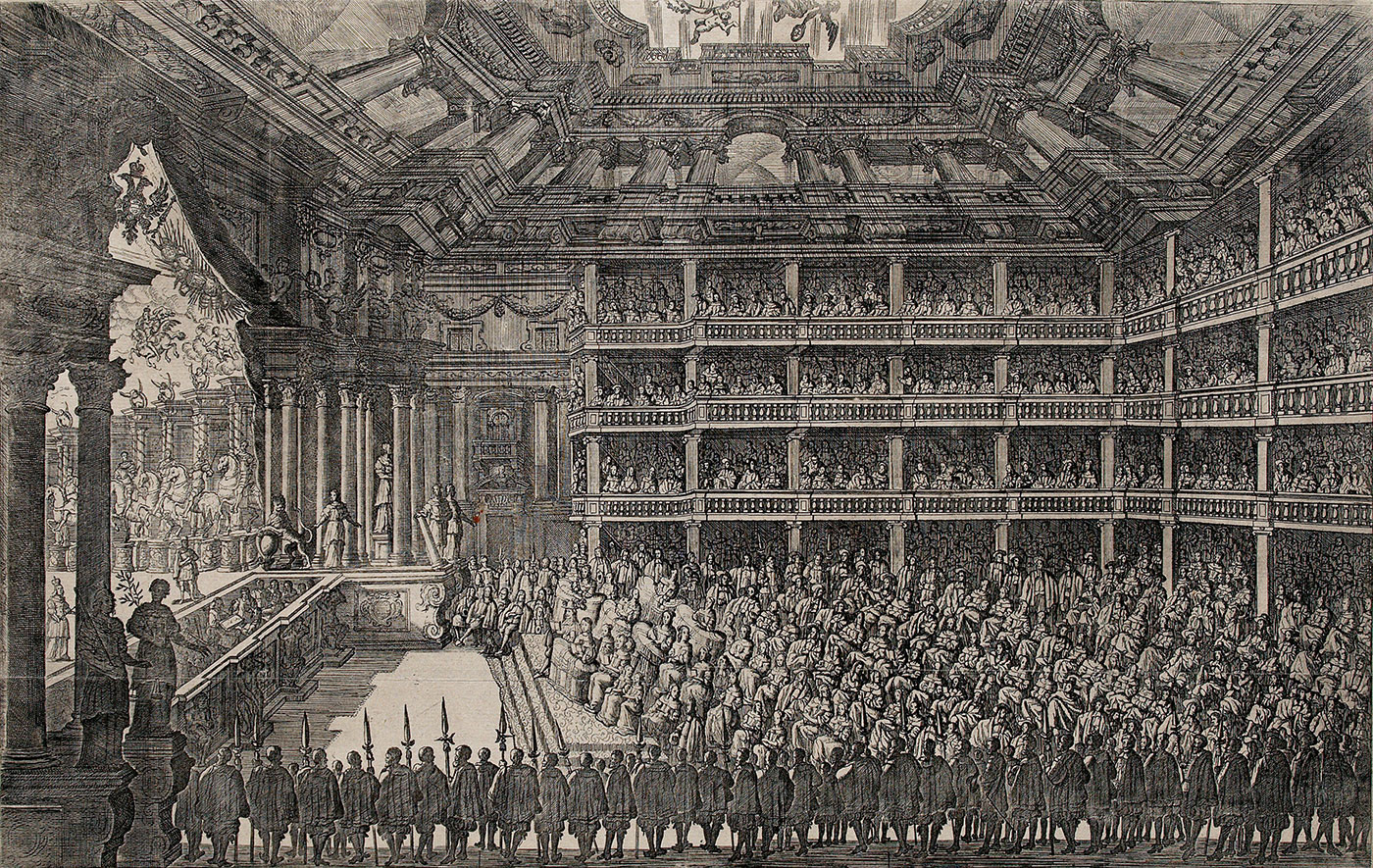

Lodovico Ottavio BURNACINI (1636-1707)

Court theatre on the castle wall in Vienna (1668)

40 x 54.6 cm

Copperplate engraving on paper

GS_GFeS3322_2

Engraving by Franz GEFFELS (1666)

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The theatre was originally planned for the celebrations of the marriage of emperor Leopold I. and the Spanish princess Margarita Teresa in 1666. Because of several construction problems it opened not until 1668. The first production was on July 12th and 14th the opera “Il pomo d’oro” to celebrate the birthday of the young empress. The wooden building on the castle wall next to the imperial court was the first freestanding theatre building in Vienna and with 1,000 seats and a size of 65 x 27 meters it was one of the biggest theatres of its time. Facing the menace of the second Turkish siege the wooden theatre was torn down in 1683 because of the fire danger. The picture features a baroque period audience including the sovereign at a theatre especially built for courtly representation.

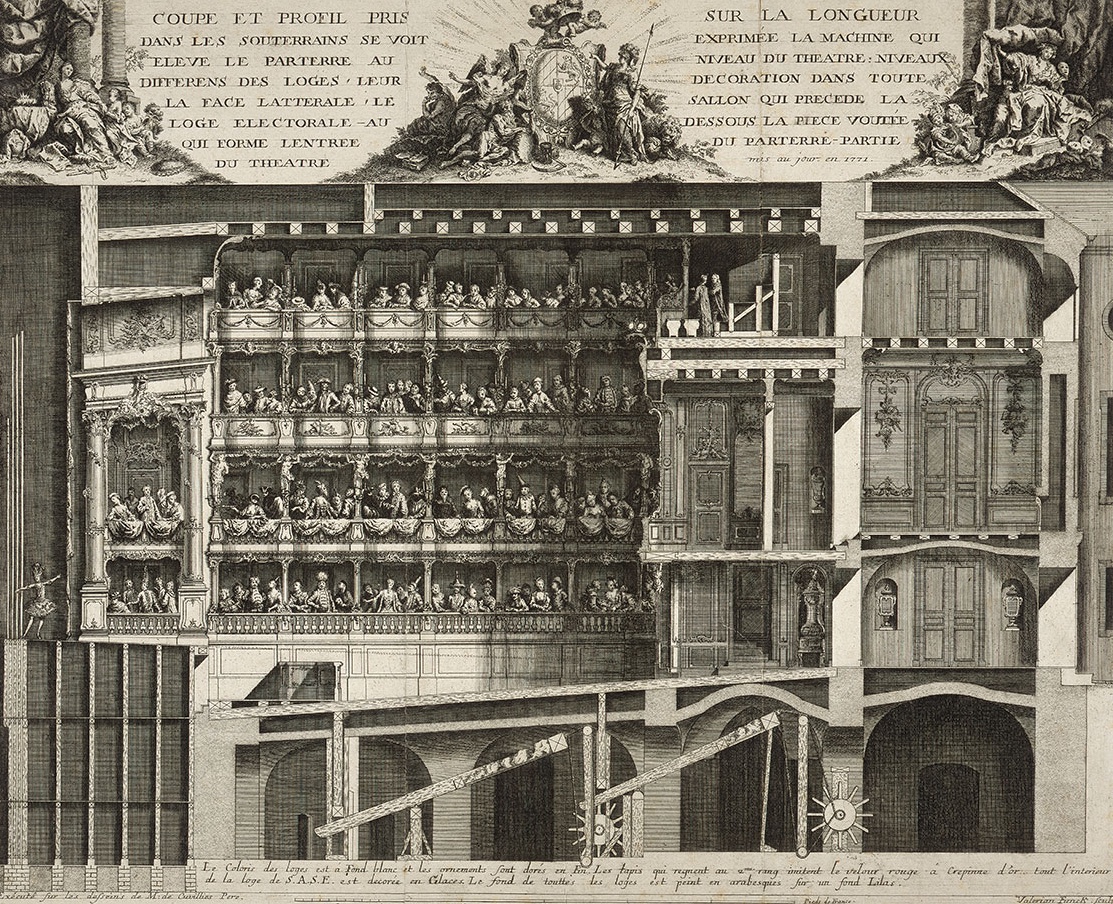

François de CUVILLIÉS (1695-1768)

Theatre of the Elector of Bavaria (Old Residence Theatre), Munich (1771)

49,5 x 68,3 cm

Engraving

VII 1102, F 833

German Theatre Museum

Engraving by Valerian Funck after François de Cuvilliés the Elder. View of the whole building including the auditorium and its floor raising mechanism.

Charles-Nicolas CHOCHIN jr (1715-1790)

Theatre in the Petits Appartements in Versailles (after 1749)

25 x 47.5 cm

Pen and ink drawing

IV 4950, F 1267

German Theatre Museum

The drawing shows a performance of “Acis and Galathea” by Jean Baptiste Lully (first performed on 23th January 1749 with Mme. Pompadour in the leading role). View of the stage and the auditorium.

Filippo JUVARRA (1678-1736)

Theatre performance at Palazzo Madama in Turin (c 1725)

32.1 x 43.5 cm

Copperplate engraving on paper

by Antoine Aveline

GS_GBU356

Theatre Museum, Vienna

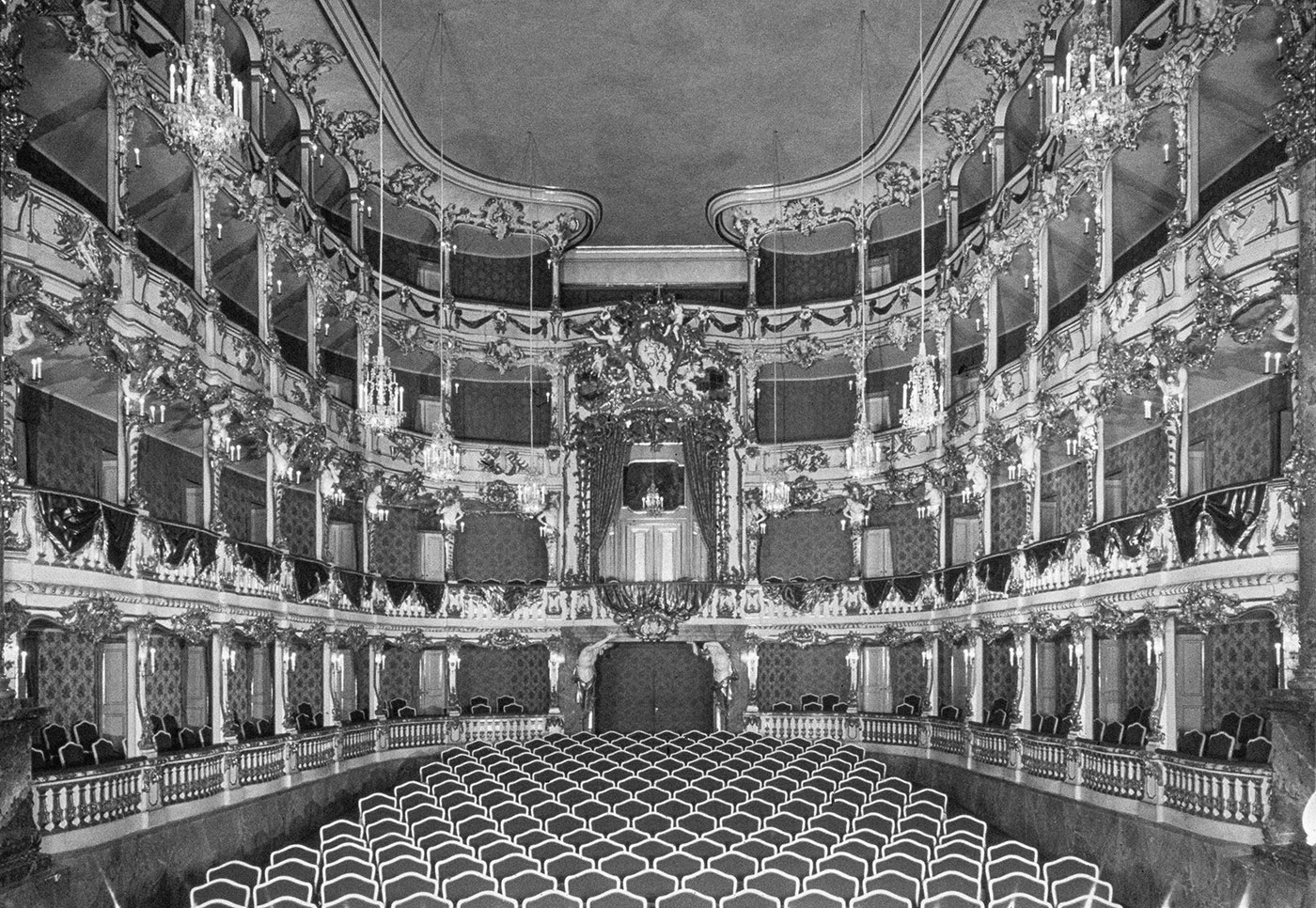

François de Cuvilliés the Elder (1695-1768)

Cuvilliés’ Theatre, Munich

Photo of the auditorium in the reopened theatre (1958)

Neg. Nr. 3024

German Theatre Museum, Munich

View into the Cuvilliés’ Theater, one of the most famous theatre interiors in Germany.

Another excellent example for the structure of balconies and boxes and the most beautiful and representative ambience for the sovereign. Adjourned reconstruction of the preserved interior décor from 1753 at the Residence in Munich after the devastation of the theatre building in the Second World War.

Giuseppe GALLI BIBIENA (1695-1757)

Carlo GALLI BIBIENA (1721-1787)

Margravial Opera House, Bayreuth (1748)

Photo

© Bavarian Palace Administration

A quintessential aristocratic theatre of the Baroque where every detail refers to the Margravial couple sitting in the royal box. The architects Giuseppe Galli Bibiena and Carlo Galli Bibiena based this interior on designs of the former’s uncle Francesco for the Emperor’s opera house in Vienna (1704), thereby connecting the court of Bayreuth with the imperial court in Vienna. The exterior was designed by Joseph-Saint Pierre, which makes the building a unique combination of sober French Baroque on the outside and voluptuous Italian Baroque inside. In 2012, the Margravial Opera House was proclaimed a UNESCO World heritage.

Most of Europe was ruled for centuries by an aristocracy which built its very own theatres. The ruler obtained a special position in this theatre: either in a central box opposite the stage, or on a raised platform in the parterre, or in a box next to the stage. The first two positions gave him a perfect view of the stage, and all three ensured that he would be seen by many members of the audience throughout the performance.

Since the 17th century, theatres of the nobility were usually Italian style opera houses. They featured rows of boxes, although the idea behind boxes – to sell tickets at a higher price – was no concern in court theatres. A special mechanism allowed raising the parterre to stage level, so that both would form a huge ballroom, e.g. in the Cuvilliés Theatre in Munich (above and left).

A world heritage from the age of Baroque:

the Margravial Opera House in Bayreuth, Germany (right).

For smaller and very private theatres, the French aristocracy developed an auditorium with just one balcony. It still featured a central box, for the owner or the visiting king. Above: a performance in Versailles in 1749, with the view of the stage turned by 90°.

Also possible were performances in private rooms, on a makeshift stage, e.g. in a palace in Turin, Italy, in 1725.

N.N.

The interior of the National Theatre on Krasiński Square in Warsaw (c 1790)

62 x 49 cm

Oil on canvas

Mp 128949

National Museum, Warsaw

The painting depicts a ballet scene from opera “Pirro” by Giovanni Paisiello. On the back side of the painting there is a list of names of the most important members of the audience (e.g. King Stanislas August) and of the dancers presented on stage: Michałek (Michał Rymiński), Sitańska (Dorota), Malińska (Marianna). Another inscription says: Scena Narodowa Warszawska 1790 ru; Kanaletty. Because of the last one the painting was previously considered to be painted by Canaletto.

At the end of the 18th century, theatres of the nobility opened to the public. At first, entrance was free, later an admission fee was introduced to pay for more frequent performances. This was also the development at the royal theatre in Warsaw, shown above during a performance in 1790. In those days, the candles in the auditorium remained lit throughout the performances; spectators could see each other and read the libretto.

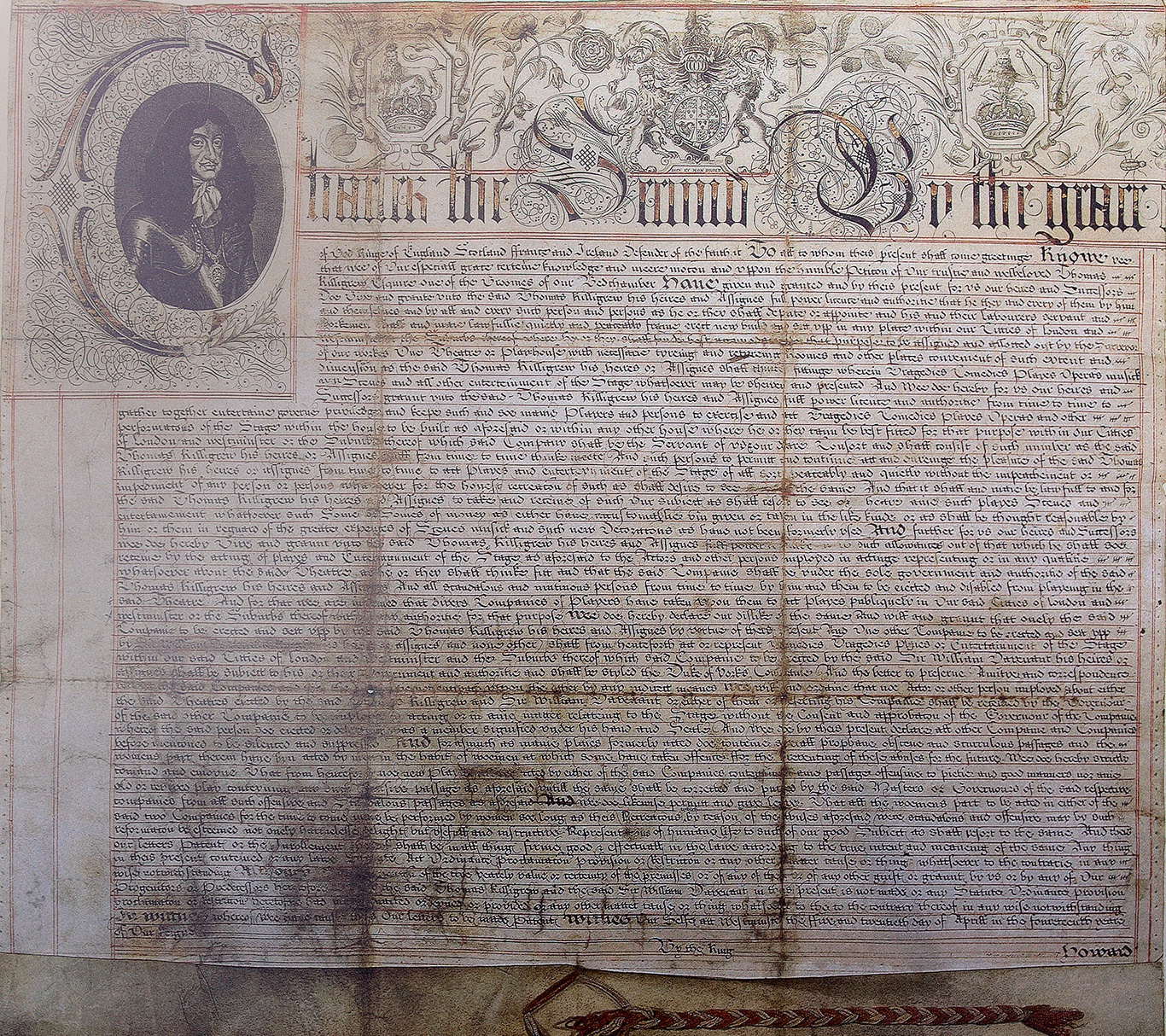

CHARLES II of England (1630-1685)

Patent for Theatre Royal Drury Lane issued to Thomas Killigrew (1662)

Brush, pen and ink on vellum, with fragment of wax seal attached by woven thread

Original on long-term loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum

© The Really Useful Theatres Group Ltd

After the start of the British civil war in 1642 and under the rule of Puritan Oliver Cromwell, British theatres were closed and Shakespearean drama forbidden, as a morally subversive and politically dangerous entertainment. After Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, he issued this Patent to two famous playwrights of his time, Charles Davenant and Thomas Killigrew, effectively allowing drama performances in Britain to again be shown. The Royal Theatre Drury Lane and the Duke’s Theatre in Dorset Garden (today’s Royal Opera House) were from that time until the 19th Century, the only theatres entitled to perform drama.

Commercial theatres existed alongside court theatres, but were regulated by the state and at times suppressed completely. The Royal Patent from 1662 is the birth certificate of London’s West End, as the two companies approved here built theatres that still exist today: Drury Lane and Covent Garden. But it also limited the number of companies entitled to play Shakespearean drama to these two – for the whole of London! Similar restrictions appeared all over Europe, as long as theatre was considered to be potentially dangerous.

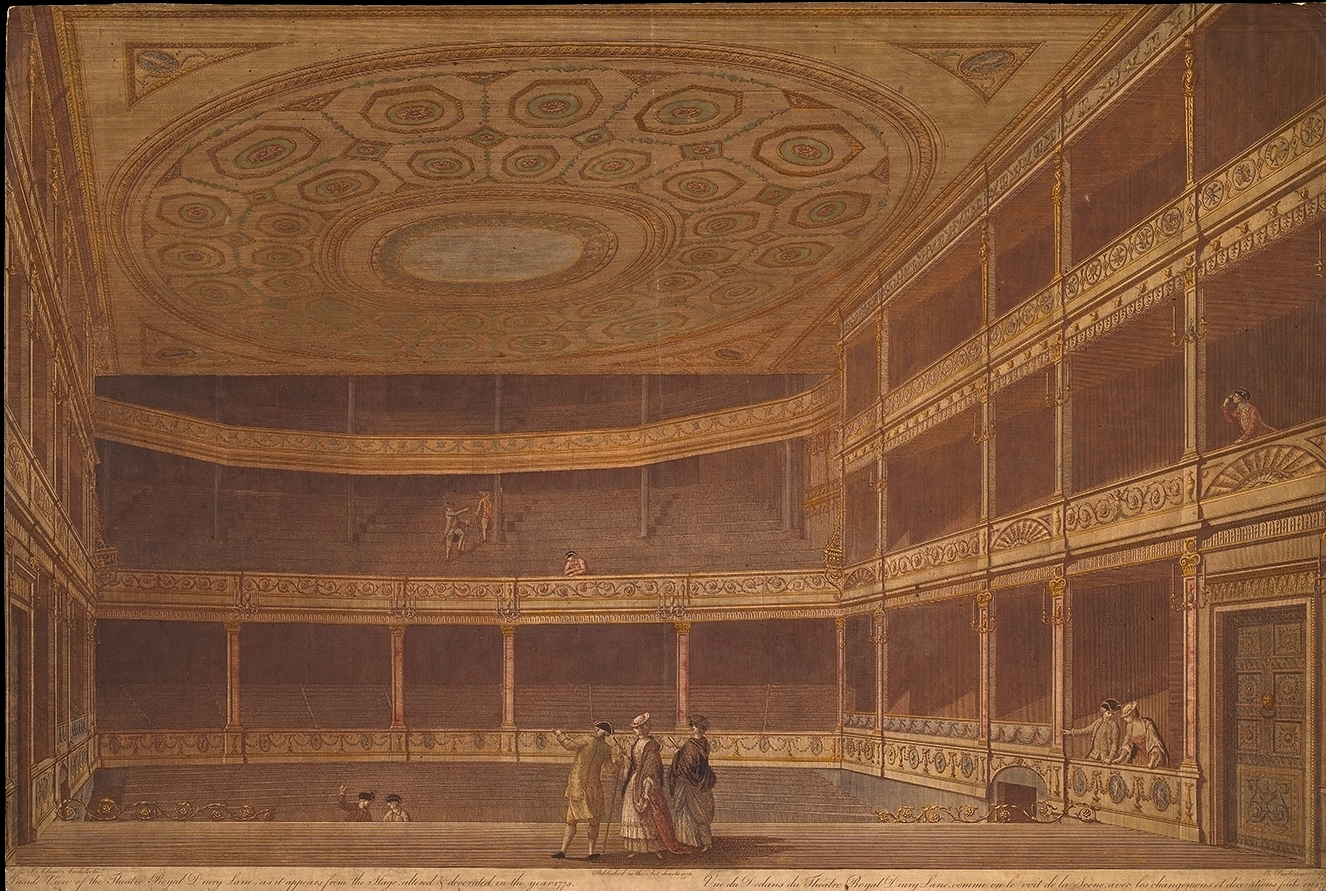

Robert ADAM (architect, 1732–1794)

James ADAM (architect, 1728–1792)

Drury Lane Interior (1775)

37.7 x 56.2 cm

Hand coloured sepia etching

Engraved by Benedetto Pastorini

S.2174-2009

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

One of David Garrick’s achievement as manager of Drury Lane was the changes he brought to the way British theatre interacted with the public. Until the 18th Century, spectators could sit more or less anywhere, including near and sometimes on the stage. Garrick introduced the barrier between pit and orchestra (which you can see also in exhibit S.55-2008), effectively separating audience and performers; he also developed the tradition of lowering the lights in the auditorium – before him auditoria were fully lit and the audience could read the script that was sold in the theatre. This print shows the refurbished interior in 1775 and a view of the auditorium from the stage, exemplifying the kind of set up that we still find today in London theatres.

Robert ADAM (architect, 1732–1794)

James ADAM (architect, 1728–1792)

View of the New Front towards Bridges Street of the principal Entry to the Theatre Royal Drury Lane (1776)

63.4 x 47.9 cm

Engraving by P. Begbie

Published by John Cawthorn

S.98-2010

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Under the leadership of famous Shakespearean actor David Garrick. The Royal Theatre Drury Lane flourished, developing the fame of Shakespeare as Britain’s best known playwright and also staging the first Pantomimes ever. In 1775, Garrick commissioned architects the Adam brothers to refurbish the interior of the building. They also created this grand façade, bringing the frontage of the building directly onto the street (as the building was built at the centre of block, originally it was set back slightly from the street) and allowing an interior hallway and office spaces.

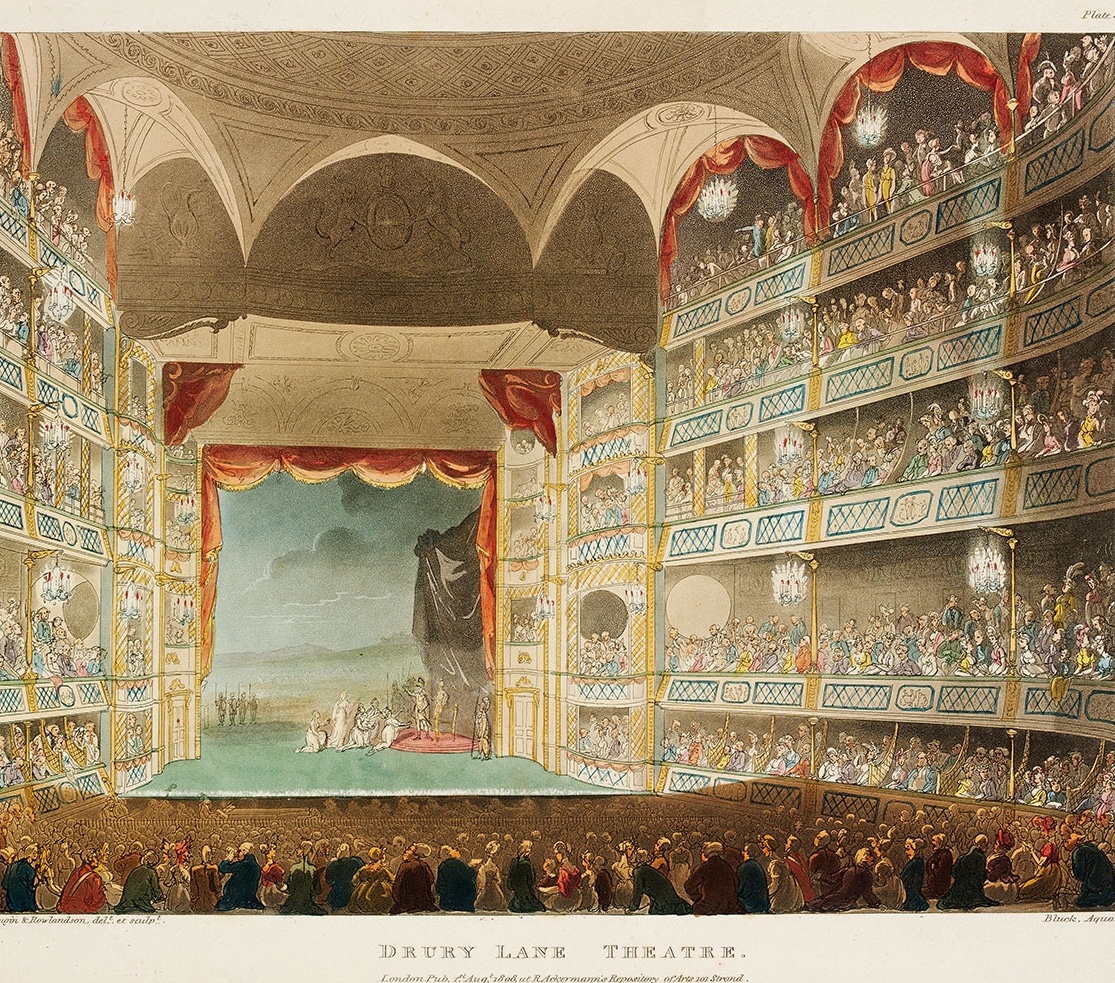

Henry HOLLAND (architect, 1745–1806)

Augustus-Charles PUGIN (artist, 1769-1832)

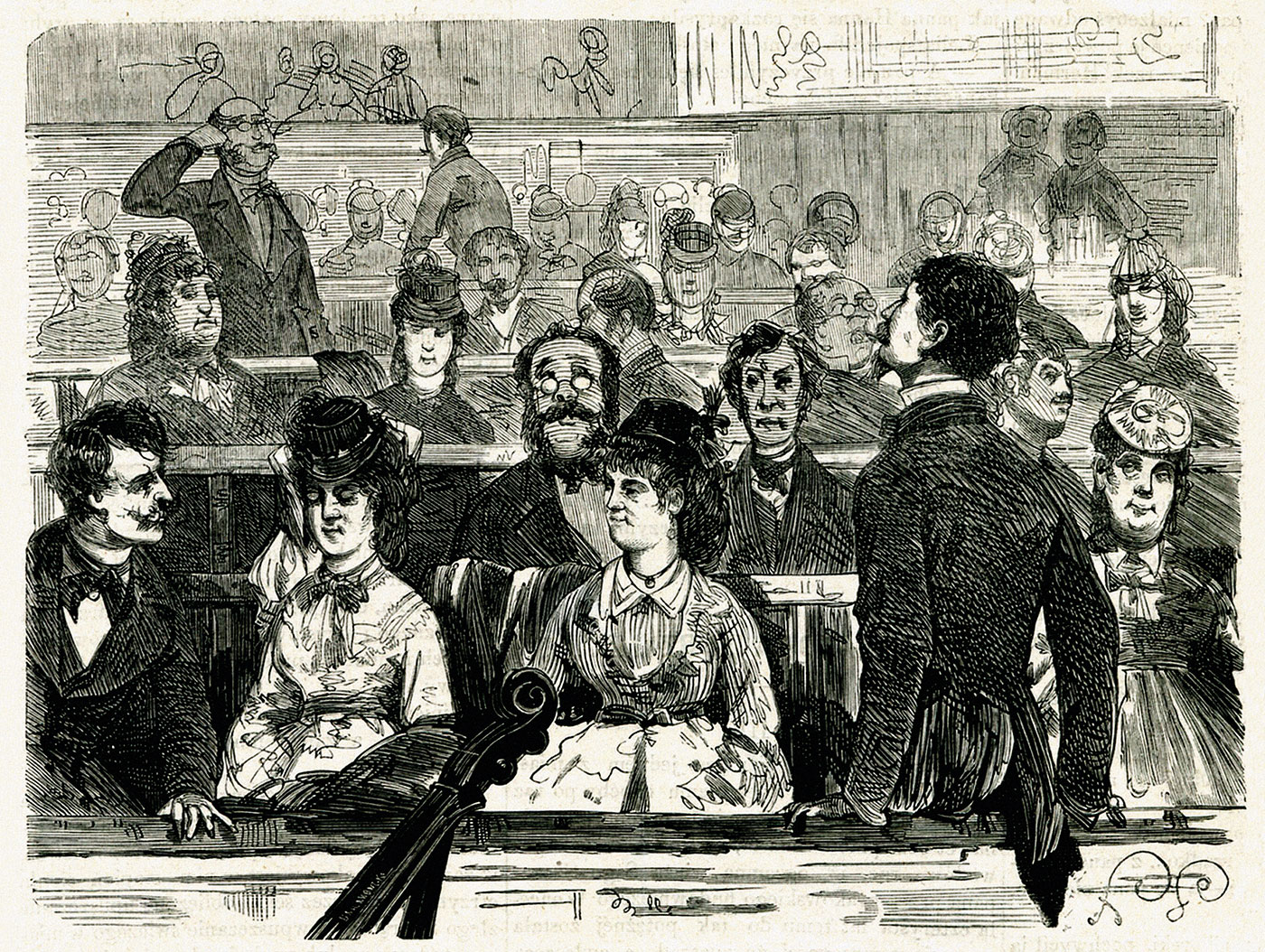

Drury Lane Interior with four Balconies (1808)

27 x 33.3 cm

Hand-coloured aquatint print

Engraving by Thomas Rowlandson

S.37-2008

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In 1778, playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan acclaimed for his School for Scandal (1777), bought Garrick’s shares in Drury Lane. He hoped the theatre would bring him sufficient income to sustain his political career begun in 1780. This led him to demolish Garrick’s theatre to build the third incarnation of Drury Lane –which opened on 12 March 1794, and was on a larger scale than any other theatre in Europe. You can see in this print the four balconies increasing the seating capacity, the barrier between the audience and the orchestra and the general crowd of a busy night featuring a Shakespeare drama. Despite these improvements and many successes, when the theatre burnt down in 1809, Sheridan was left bankrupt.

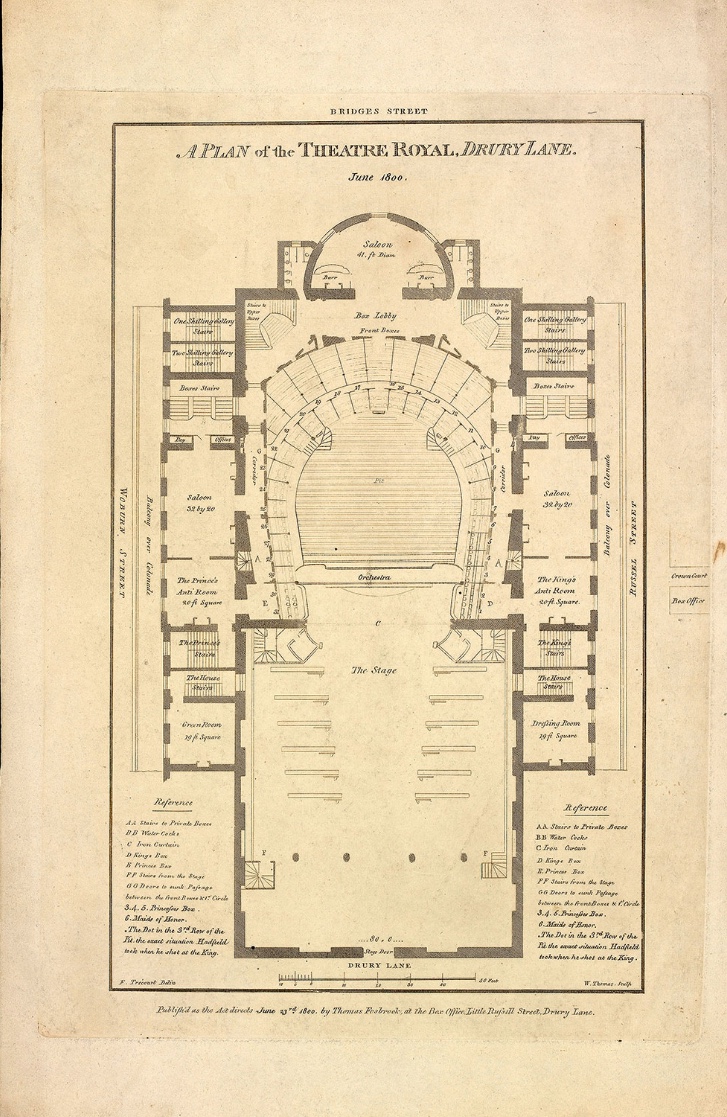

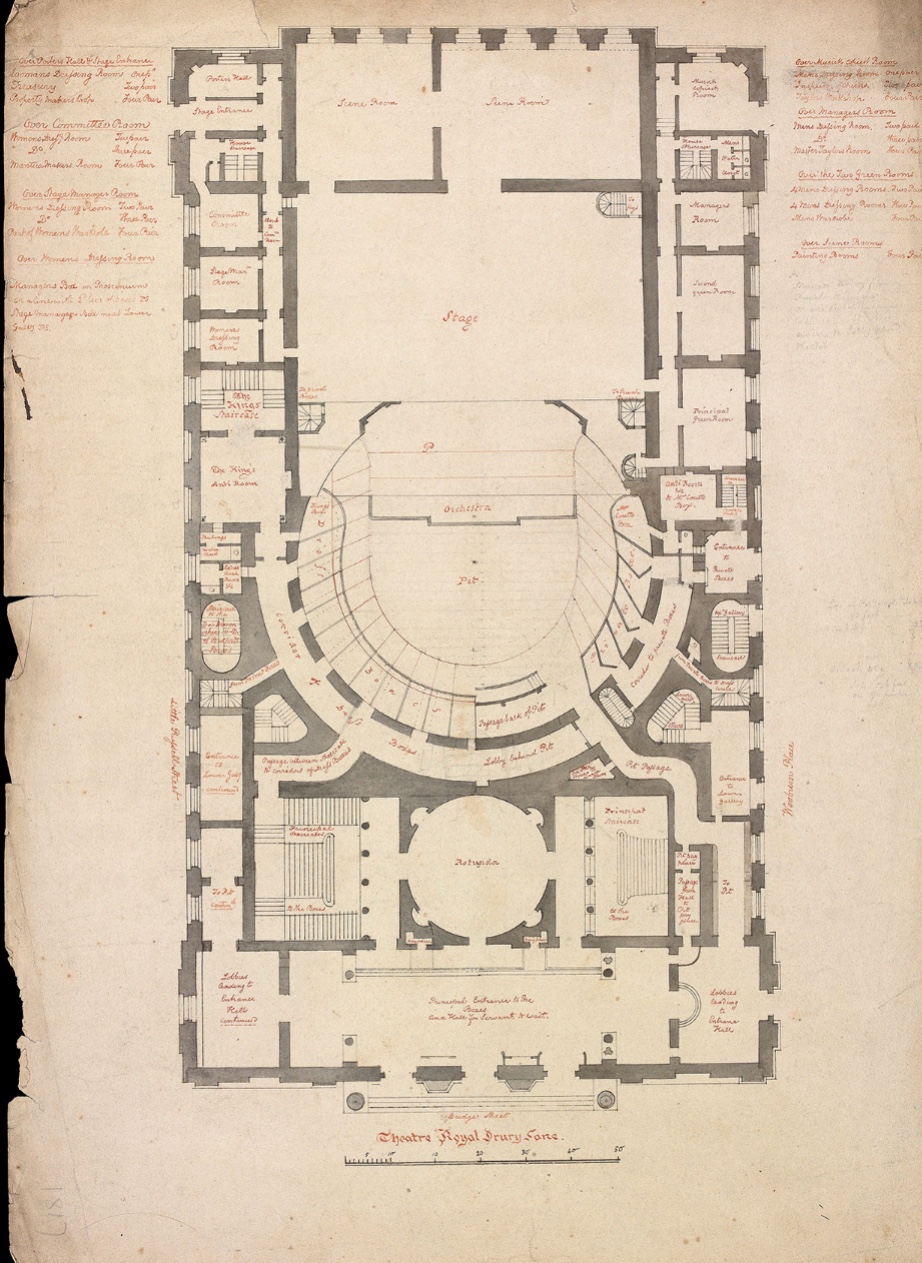

Henry HOLLAND (architect, 1745–1806)

Jean Pierre Théodore TRÉCOURT (draughtsman)

Plan of Drury Lane (1800)

42.9 x 28.5 cm

Engraving, ink on paper

Engraving by W. Thomas published by Thomas Fosbrook

S.230-1984

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This plan shows Richard Sheridan’s Drury Lane, designed by architect Henry Holland. The new theatre used some of the advanced technology newly available at the time, such as iron replacing wood for the columns and thus supporting five tiers of galleries. It also featured the newest machinery and bridges, traps and wings, marketing spectacular mise-en-scène and ambitious productions rather than the intimacy between public and performance which prevailed in Garrick’s day. Stage and auditorium were separated by a cross wall and fire curtain, which unfortunately didn’t prevent the theatre from burning to the ground in 1809.

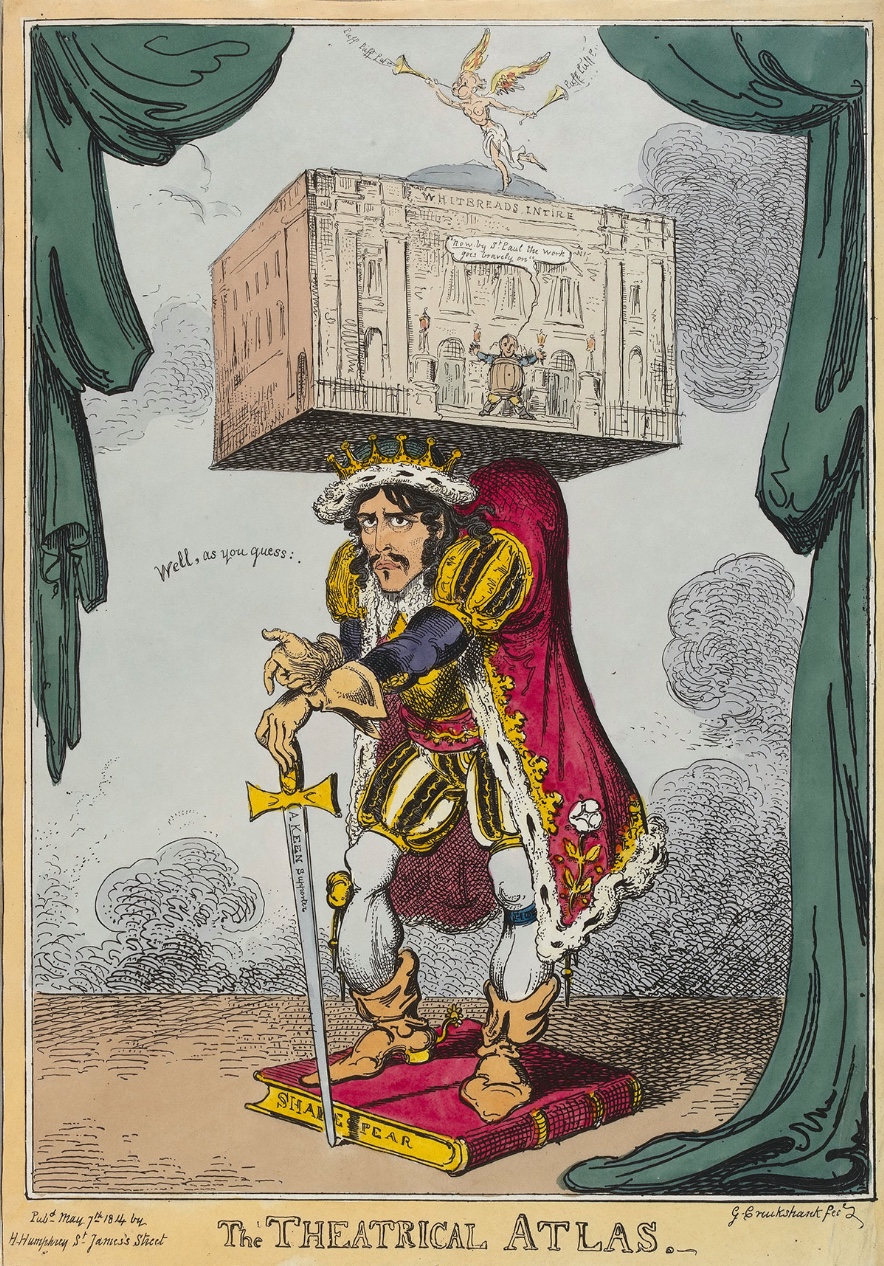

George CRUIKSHANK (1792-1878)

“The Theatrical Atlas” (1814)

36.7 x 26.7 cm

Hand coloured etching

Published by H. Humphrey

S.99-1992

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In 1814 the theatre was again nearing bankruptcy and the committee brought in Edmund Kean, at the time an unknown actor, as an experiment to reverse their fortunes. The brilliant but unpredictable and wayward Kean achieved his first success as Shylock in 1814, bringing back the audience to the theatre and successively drawing the crowds through his portrayals of Othello, Richard III, Macbeth and Hamlet. Here dressed as Richard III, he is satirically depicted supporting the entire theatre on his own.

Benjamin WYATT (architect, 1775–1852)

James WINSTON (draughtsman)

Plan of Drury Lane (1820)

44.2 x 24.4 cm

Pen and ink, pencil and washes on paper

S.35-1984

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Following the fire, Benjamin Wyatt’s building, was delivered in 1812 and still stands today on Catherine Street at the edge of London West End. Although slightly smaller than Sheridan’s building, the new theatre retained the separation between actors and audience. The proscenium arch acted as a frame to the stage, and the auditorium was renamed the ‘Spectatory’.

The theatre is unique in having two Royal boxes with separate staircases departing from the foyer. One of the boxes is the King’s and the second the Prince of Wales’s, created because of bad feeling between George III and his son which led to an assault between them during a visit to the theatre.

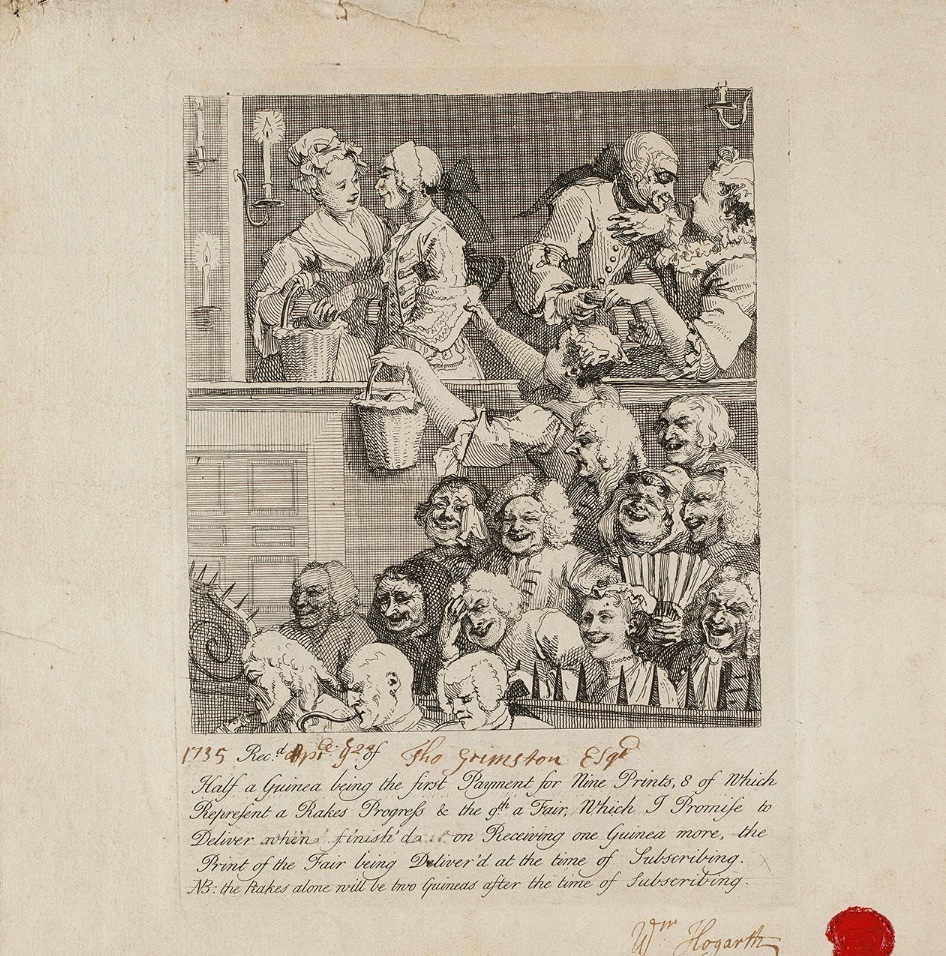

William HOGARTH (1697-1764)

The Laughing Audience (1735)

27 x 26 cm

Engraving on paper, with wax seal and manuscript

S.55-2008

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This print reproduces an engraving by painter William Hogarth, famous for his depictions of his contemporaries, in paintings and engravings, in ironic and often moralistic settings. Here the audience of an 18th Century theatre is featured, showing the occupants of the cheap seats in the pit laughing out loudly at the funny play, while aristocratic members of the public in the background are clearly involved in anything else but the play. One of the three orchestra members at the front has removed his wig for more comfort. Theatre has always been a social event and here is an example of how society of all levels interacted with theatre in the 18th Century.

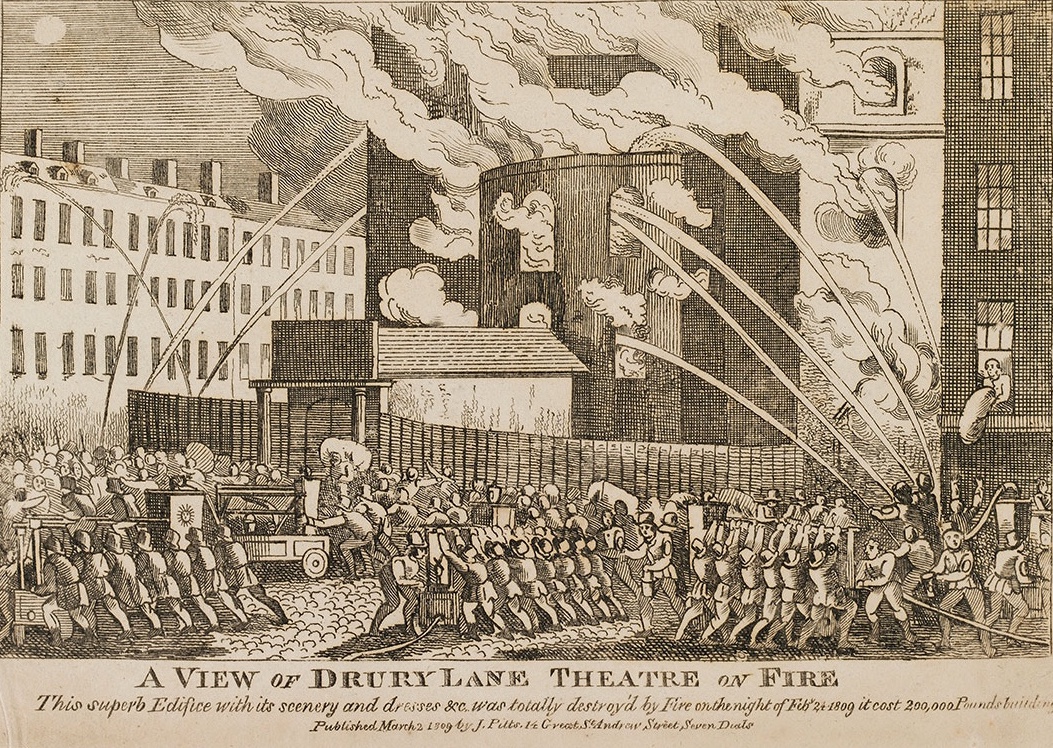

N.N.

Drury Lane on Fire (1809)

17.3 x 14.8 cm

Engraving

Published by J. Pitts, London

S.527-1997

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This engraving shows the Theatre Royal Drury Lane on fire on the 24th of February 1809, as published in the following week’s newspapers. Although it was fitted with the fire-prevention technology available at the time, it was insufficient, and the owner Richard Sheridan was left penniless, thus ruining his political carrier which relied on the theatre for financing. While he drank and watched the theatre burning down, he is reputed to have said:

“A man surely can be allowed to take a glass of wine by his own fireside.”

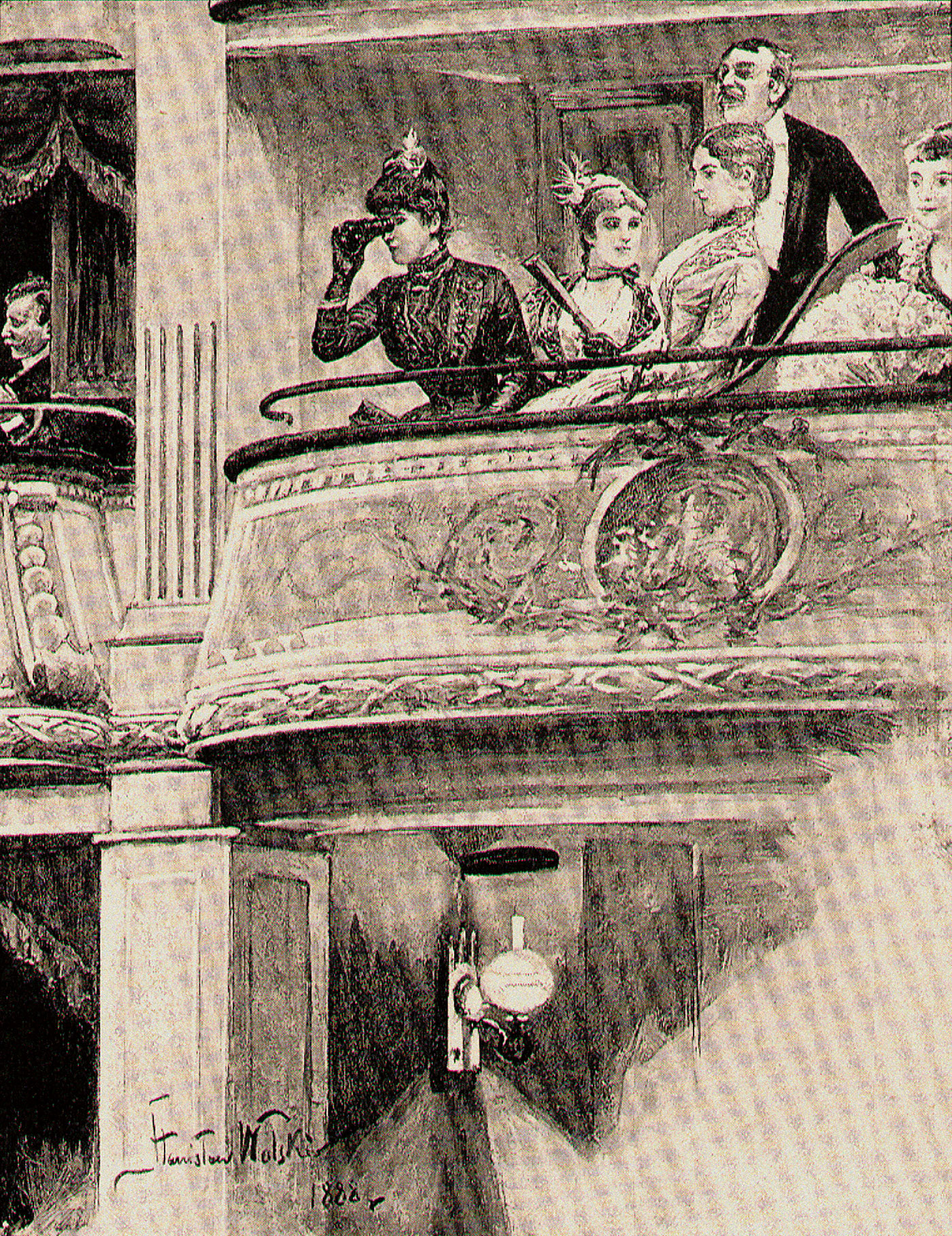

Stanisław Pomian Wolski (1859–1894)

Theatre Box (1888)

13 x 17 cm

Print on paper

Theatre Museum, Warsaw

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as “Drury Lane”, is located in the London West End. Since 1663, four consecutive theatre buildings were erected in this location, making it the oldest theatre site in continuous use in London. The first building burned down already in 1672. Two years later, the second theatre was inaugurated.

Above: the auditorium in 1775 and the new façade of 1776, after the refurbishment under David Garrick’s management.

Playwright, proprietor and manager Richard Sheridan demolished the second theatre in 1791 and opened the third one in 1794 (views of the interior 1808 and floor plan 1800). Designed to increase the seating capacity and thus its financial gains, this theatre burned down in 1809, leaving Sheridan bankrupt.

Bottom left: 18th century audience by William Hogarth.

Bottom right: 19th century audience and gas light.

The appearance of the leading Shakespeare actor Edmund Kean (1787-1833), caricatured here as Richard III, secured the future of the fourth Drury Lane theatre. It opened in 1812 and accommodated over 3000 spectators. The floor plan (1820) shows one royal box left and right of the stage – one for the king and one for the heir to the throne, who did not want to meet each other. This building still stands today.

Rudolf von ALT (1812 – 1905)

The Burgtheater on Michaeler Square in Vienna (c 1860)

43.7 cm x 59.5 cm

Lithography on paper

by Franz Joseph Sandmann

GS_GBS3810

Theatre Museum, Vienna

On this historical view of the Michaeler Square in Vienna the theatre is the small building in the centre. It was originally constructed as “Ballhaus” (a building for playing ball games) and converted into a theatre between 1741 and 1748. It was the court theatre and also had a close architectural connection to the buildings of the imperial court (German: “Hofburg”, or just “Burg”) and therefore it was named “Burgtheater”. In 1888 it was torn down because it was not possible to adapt the building to the needs of the expanding city, its growing theatre audiences and to the new technical and aesthetical standards. The new Burgtheater was erected at the Ringstraße vis-à-vis the town hall – it is still called “Burgtheater” after its predecessor.

N.N.

The Burgtheater on Ringstrasse in Vienna

(c 1920)

20.8 x 26.9 cm

Photo on paper

FS_PBM165495

Theatre Museum, Vienna

Vienna during in the second half of the 19th century is a very striking example of how the changes in society (industrialization and growing cultural, social, and economic strength of the middle class) led to changes in the whole structure and architecture of a city (city expansion, demolition of the city walls, formation of new streets and boulevards). This change also concerned the old court theatres: both moved from the inner city to the new created boulevard, the Ringstrasse, where most of the representative new buildings where erected.

Kurt Hoppe RODAHL

The Royal Theatre, Copenhagen

Photo (2013)

Theatre Museum at the Court Theatre, Copenhagen

Nowadays, The Royal Theatre in Copenhagen Denmark is made up of three main buildings: Old Stage at King’s New Square (designed by architects Wilhelm Dahlerup and Ove Petersen), opened in 1874 and still in existence; the New Playhouse from 2008 (designed by architexts Lundgaard & Tranberg ) and the Opera from 2005 (architect Henning Larsen). The Playhouse and the Opera House are two of Denmark’s most recent, most expensive and most exciting cultural institutions. They are positioned on either side of Copenhagen’s Canal. The Playhouse is situated at the “Kvæsthus” bridge at the end of Nyhavn. The Opera House is situated diagonally across on “Holmen”, the old navy installations, which is now full of cafés, modern housing and cultural institutions. The Playhouse houses all of three stages under one roof. The new Royal Opera building from 2005 or The Opera House is the national opera house of Denmark, and among the most modern opera houses in the world. It is also one of the most expensive opera houses ever built with construction costs well over 500 million U.S. dollars – it has created a lot of political and cultural debate.

Kurt Hoppe RODAHL

The new Playhouse

Photo (2013)

Theatre Museum at the Court Theatre, Copenhagen

Nowadays The Royal Theatre in Copenhagen Denmark is made up of three main buildings: Old Stage at King’s New Square (designed by architects Wilhelm Dahlerup and Ove Petersen), opened in 1874 and still in existence; the New Playhouse from 2008 (designed by architexts Lundgaard & Tranberg ) and the Opera from 2005 (architect Henning Larsen). The Playhouse and the Opera House are two af Denmark’s most recent, most expensive and most exciting cultural institutions. They are positioned on either side of Copenhagen’s Canal. The Playhouse is situated at the “Kvæsthus” bridge at the end of Nyhavn. The Opera House is situated diagonally across on “Holmen”, the old navy installations, which is now full of cafés, modern housing and cultural institutions. The Playhouse houses all of three stages under one roof. The new Royal Opera building from 2005 or The Opera House is the national opera house of Denmark, and among the most modern opera houses in the world. It is also one of the most expensive opera houses ever built with construction costs well over 500 million U.S. dollars – it has created a lot of political and cultural debate.

Kurt Hoppe RODAHL

The new Royal Opera building

Photo (2013)

Theatre Museum at the Court Theatre, Copenhagen

Nowadays, The Royal Theatre in Copenhagen Denmark is made up of three main buildings: Old Stage at King’s New Square (designed by architects Wilhelm Dahlerup and Ove Petersen), opened in 1874 and still in existence; the New Playhouse from 2008 (designed by architexts Lundgaard & Tranberg ) and the Opera from 2005 (architect Henning Larsen). The Playhouse and the Opera House are two af Denmark’s most recent, most expensive and most exciting cultural institutions. They are positioned on either side of Copenhagen’s Canal. The Playhouse is situated at the “Kvæsthus” bridge at the end of Nyhavn. The Opera House is situated diagonally across on “Holmen”, the old navy installations, which is now full of cafés, modern housing and cultural institutions. The Playhouse houses all of three stages under one roof. The new Royal Opera building from 2005 or The Opera House is the national opera house of Denmark, and among the most modern opera houses in the world. It is also one of the most expensive opera houses ever built with construction costs well over 500 million U.S. dollars – it has created a lot of political and cultural debate.

Kurt Hoppe RODAHL

Auditorium of the Royal Theatre, Copenhagen

Photo (2013)

Theatre Museum at the Court Theatre, Copenhagen

Nowadays The Royal Theatre in Copenhagen Denmark is made up of three main buildings: Old Stage at King’s New Square (designed by architects Wilhelm Dahlerup and Ove Petersen), opened in 1874 and still in existence; the New Playhouse from 2008 (designed by architexts Lundgaard & Tranberg ) and the Opera from 2005 (architect Henning Larsen). The Playhouse and the Opera House are two af Denmark’s most recent, most expensive and most exciting cultural institutions. They are positioned on either side of Copenhagen’s Canal. The Playhouse is situated at the “Kvæsthus” bridge at the end of Nyhavn. The Opera House is situated diagonally across on “Holmen”, the old navy installations, which is now full of cafés, modern housing and cultural institutions. The Playhouse houses all of three stages under one roof. The new Royal Opera building from 2005 or The Opera House is the national opera house of Denmark, and among the most modern opera houses in the world. It is also one of the most expensive opera houses ever built with construction costs well over 500 million U.S. dollars – it has created a lot of political and cultural debate.

Kurt Hoppe RODAHL

Foyer of the new Royal Opera building

Photo (2013)

Theatre Museum at the Court Theatre, Copenhagen

Nowadays, The Royal Theatre in Copenhagen Denmark is made up of three main buildings: Old Stage at King’s New Square (designed by architects Wilhelm Dahlerup and Ove Petersen), opened in 1874 and still in existence; the New Playhouse from 2008 (designed by architexts Lundgaard & Tranberg ) and the Opera from 2005 (architect Henning Larsen). The Playhouse and the Opera House are two af Denmark’s most recent, most expensive and most exciting cultural institutions. They are positioned on either side of Copenhagen’s Canal. The Playhouse is situated at the “Kvæsthus” bridge at the end of Nyhavn. The Opera House is situated diagonally across on “Holmen”, the old navy installations, which is now full of cafés, modern housing and cultural institutions. The Playhouse houses all of three stages under one roof. The new Royal Opera building from 2005 or The Opera House is the national opera house of Denmark, and among the most modern opera houses in the world. It is also one of the most expensive opera houses ever built with construction costs well over 500 million U.S. dollars – it has created a lot of political and cultural debate.

Kurt Hoppe RODAHL

Auditorium of the new Playhouse

Photo (2013)

Theatre Museum at the Court Theatre, Copenhagen

Nowadays The Royal Theatre in Copenhagen Denmark is made up of three main buildings: Old Stage at King’s New Square (designed by architects Wilhelm Dahlerup and Ove Petersen), opened in 1874 and still in existence; the New Playhouse from 2008 (designed by architexts Lundgaard & Tranberg ) and the Opera from 2005 (architect Henning Larsen). The Playhouse and the Opera House are two af Denmark’s most recent, most expensive and most exciting cultural institutions. They are positioned on either side of Copenhagen’s Canal. The Playhouse is situated at the “Kvæsthus” bridge at the end of Nyhavn. The Opera House is situated diagonally across on “Holmen”, the old navy installations, which is now full of cafés, modern housing and cultural institutions. The Playhouse houses all of three stages under one roof. The new Royal Opera building from 2005 or The Opera House is the national opera house of Denmark, and among the most modern opera houses in the world. It is also one of the most expensive opera houses ever built with construction costs well over 500 million U.S. dollars – it has created a lot of political and cultural debate.

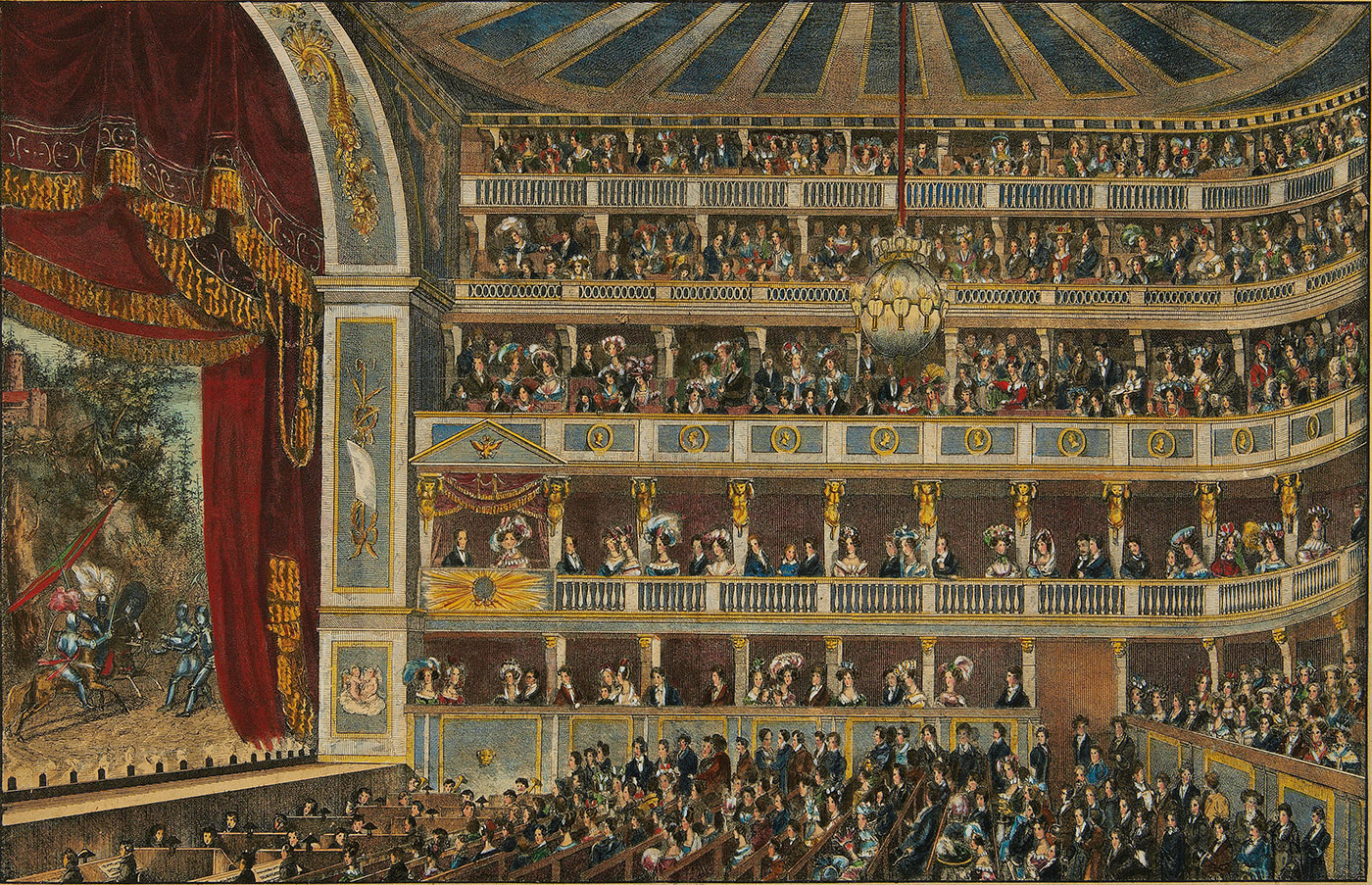

N.N.

Auditorium of the “Theater an der Wien” (1831)

41.9 x 60.2 cm

Coloured lithography on paper

GS_GBS5730

Theatre Museum, Vienna

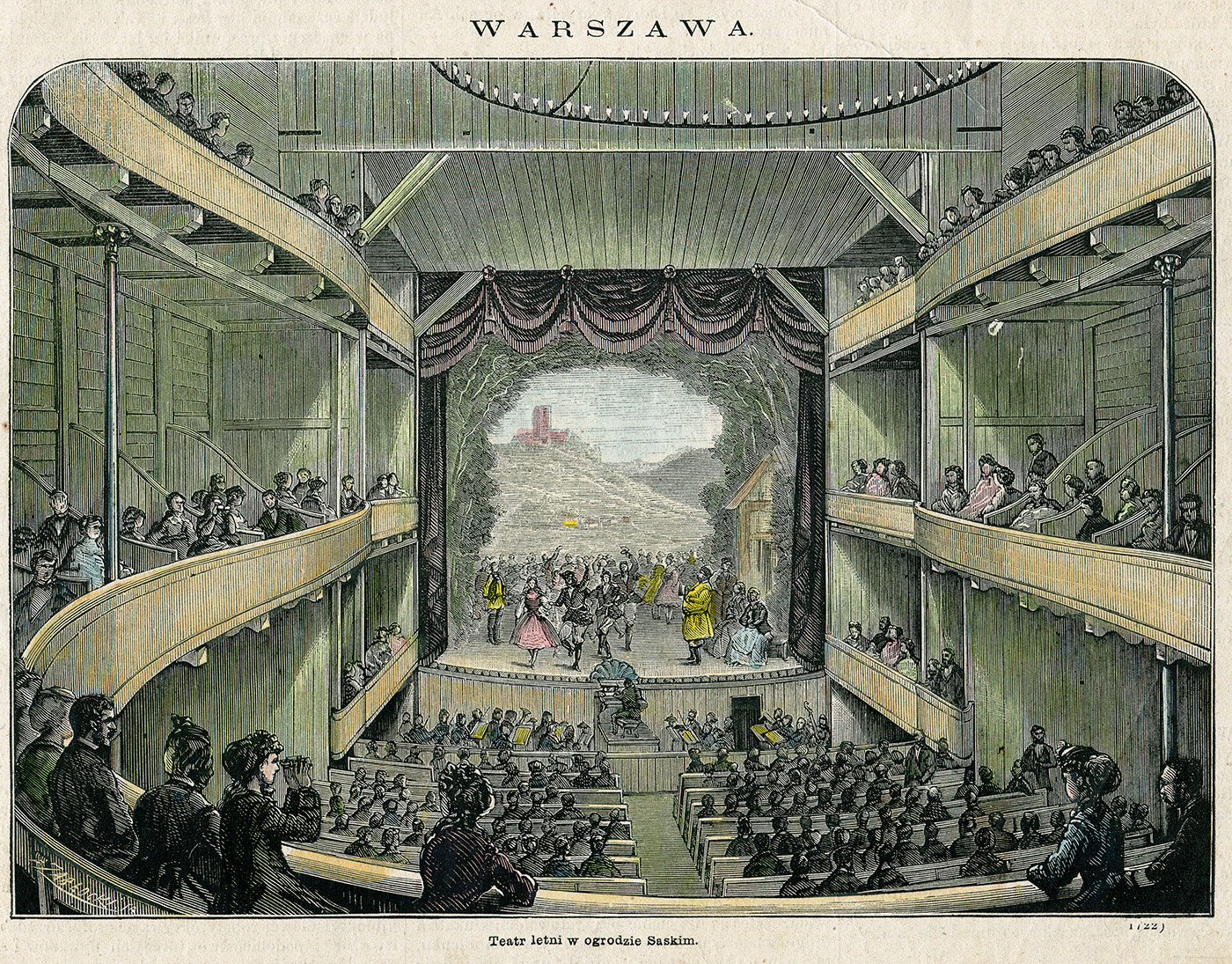

Feliks ZABŁOCKI (1846-1874)

Summer Theatre in Saxon Garden, Warsaw (1870)

“Kłosy”1870 t. XI

25 x 27 cm

Print on paper

MT/III/594/11

Theatre Museum, Warsaw

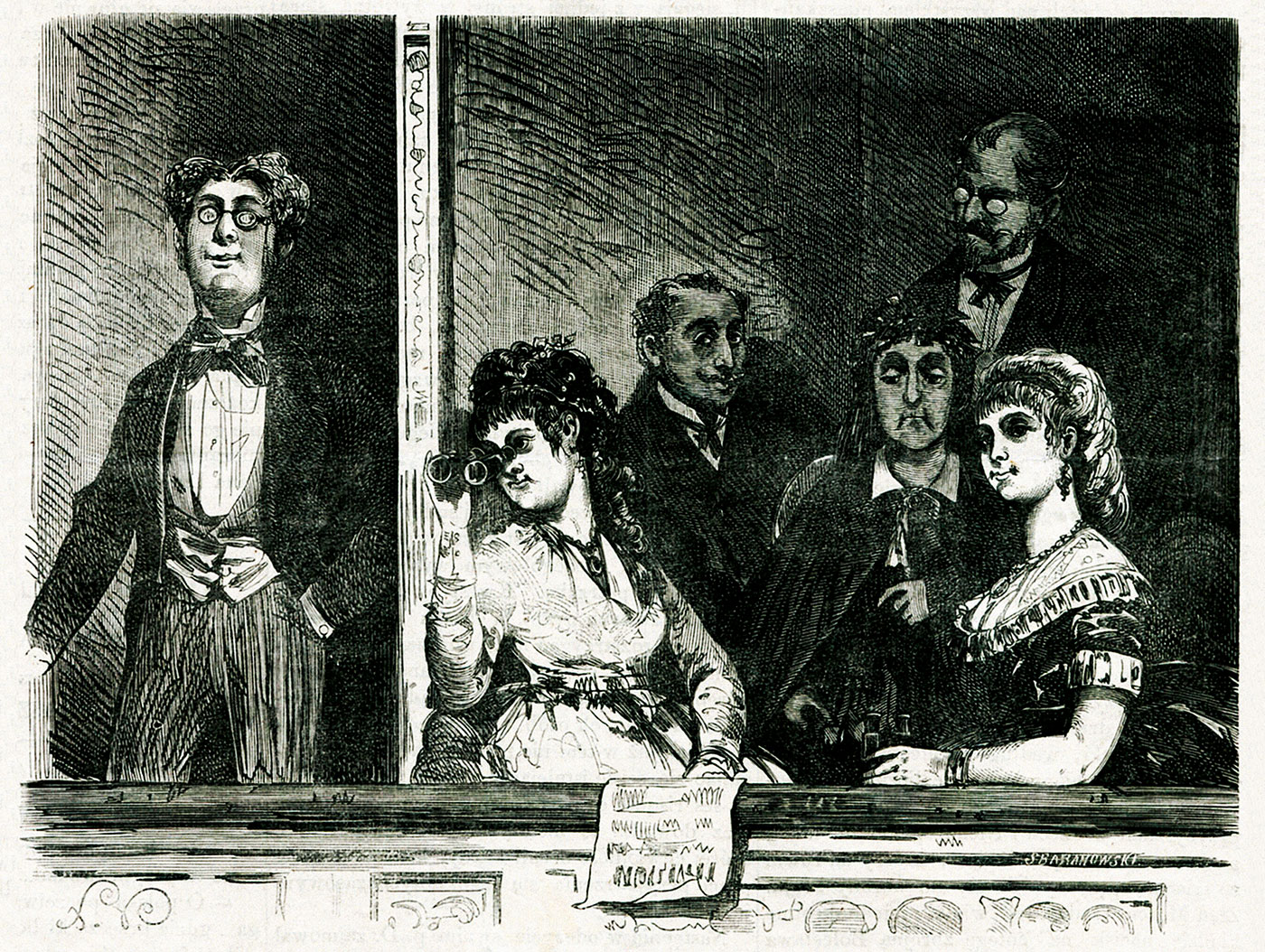

Stanisław BARANOWSKI (1850-c 1890)

Warsaw's Audience / Spectators I

Caricature

19.10 x 14.8 cm

Print on paper

Theatre Museum, Warsaw

Stanisław BARANOWSKI (1850-c 1890)

Warsaw's Audience / Spectators II

Caricature

19.10 x 14.8 cm

Print on paper

Theatre Museum, Warsaw

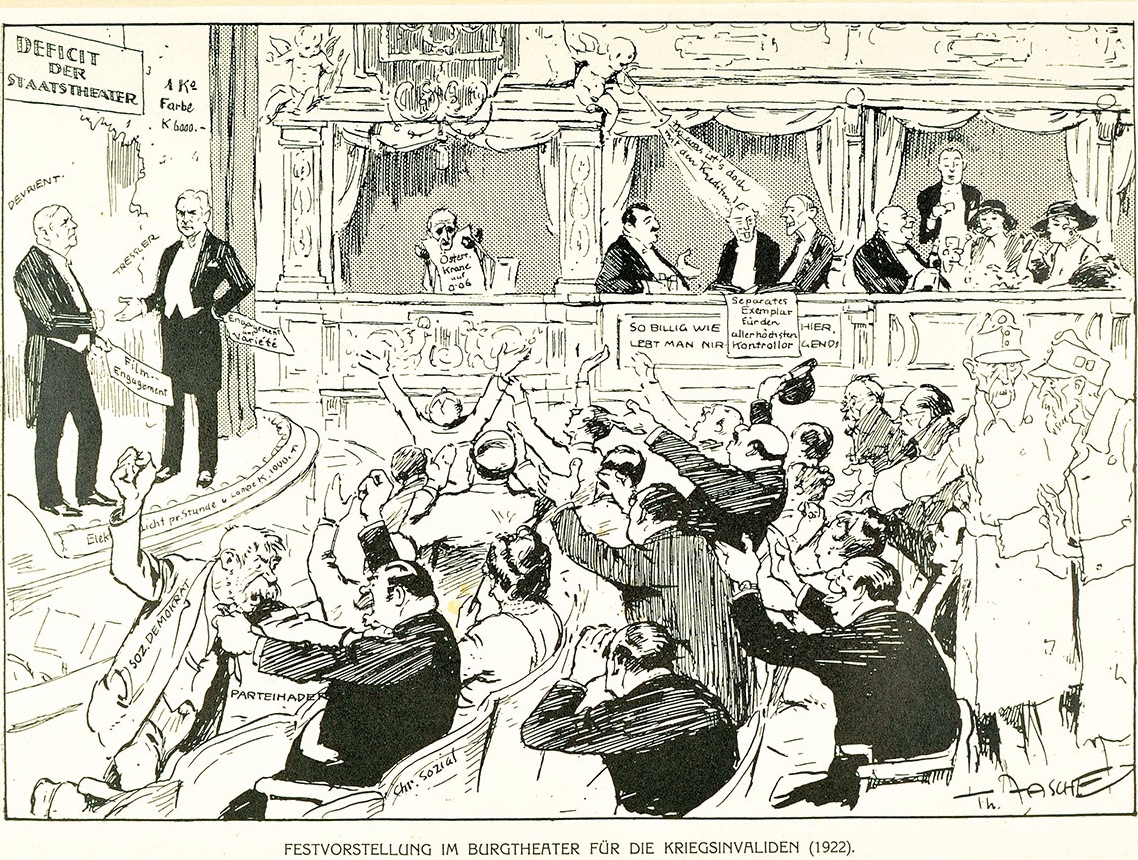

Theodor ZASCHE (1862-1922)

Gala performance at the Burgtheater in benefit for the war invalids (1922)

Caricature

33.5 x 40 cm

Lithography on paper

GS_GKarU4563

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The growing power of the bourgeoisie in the 19th century expressed itself in larger theatre buildings – compare the old Burgtheater in Vienna from 1748 (top, the small building in the centre) with the new one from 1888 (photo below).

In the 20th century, the idea of an open, democratic society led to the use of glass, e.g. in Copenhagen, Denmark, where the new opera house from 2005 (right) and the new playhouse from 2008 (centre) contrast the still existing 19th century opera house.

Whether the spectator feels more comfortable in a polished modern auditorium than in a decorated historic one, is an open question.

Bottom row: images of audiences from the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century also illustrate changes in society.

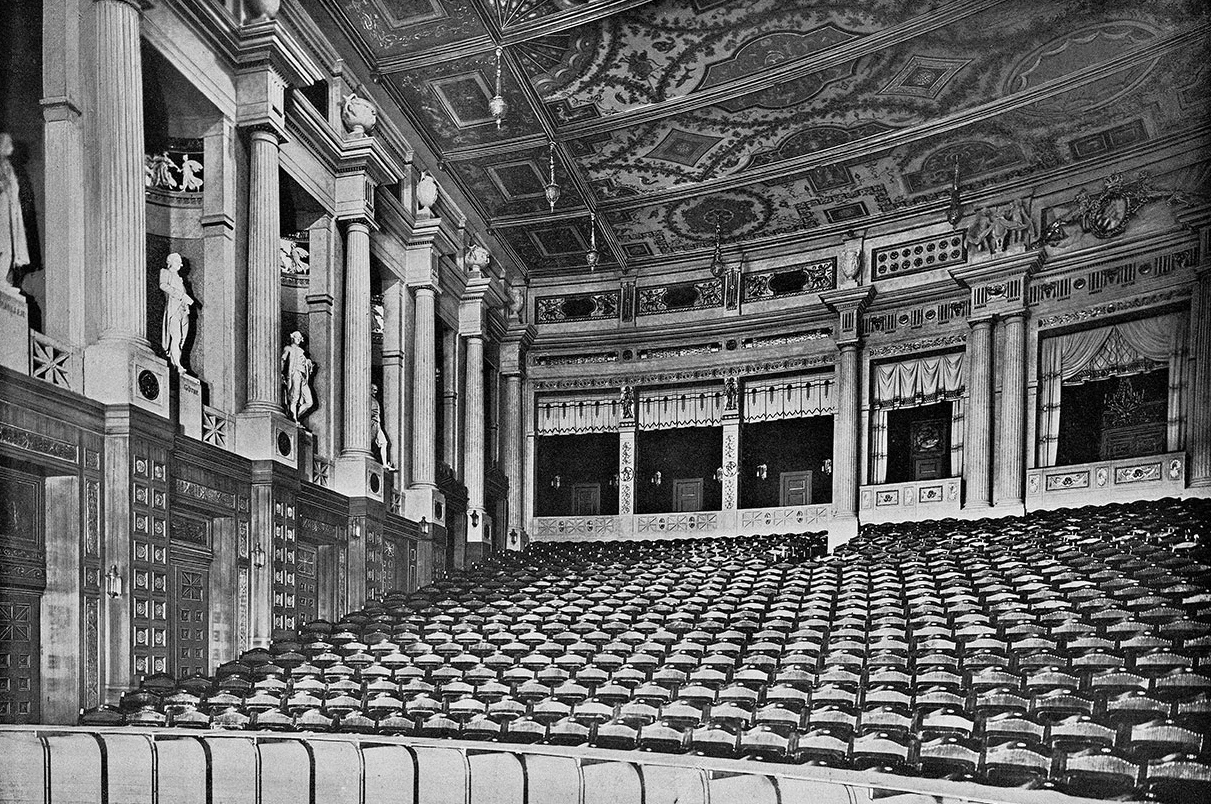

N.N.

Auditorium of the National Theatre in Munich

Photo (1963)

German Theatre Museum, Munich

This theatre opened as “Court and National Theatre” in 1818. Devastated in WWII, it was reconstructed to simplified designs, but still with a royal box, in 1963.

Max LITTMANN (1862-1931)

Prince Regent Theatre, Munich (around 1901)

Photo

in: Denkschrift Das Prinzregententheater (1901), Tafel XV

4597

German Theatre Museum, Munich

View of the auditorium. The theatre was built from 1900 to 1901. The essential renewal was the auditorium based on the architecture of ancient Greek and Roman theatres, rediscovered in the renaissance. It is not the structure of balconies and boxes of the aristocratic society but the space for a democratic community being involved in a special theatrical celebration. The only compromise was a back wall with nine boxes, three of which were exposed by a balcony. In the middle there was a box for the sovereign.

Max LITTMANN (1862-1931)

Model of the Künstlertheater Munich (1907/8)

80 x 53 x 165 cm

Partly coloured wood

Photo by Robin Rehm (2002)

F 995

German Theatre Museum, Munich

The renewal was the auditorium in the form of a continuously rising platform based on the architecture of ancient Greek and Roman theatres.

Max LITTMANN (architect, 1862-1931)

Richard RIEMERSCHMID (interior designer, 1868-1957)

Kammerspiele, Munich

Photo by Hildegard Steinmetz (1971)

Originalneg. 8365, F 19637

German Theatre Museum, Munich /Archive Hildegard Steinmetz

Another kind of auditorium was created in the “Neues Schauspielhaus” where the “Munich Kammerspiele” has been located since 1926. Built by Littmann and decorated by Richard Riemerschmid in 1901, this theatre offered an adequate framework for performances of the more intimate dramas by Henrik Ibsen or Frank Wedekind. This meant a new definition of the relationship between stage and audience.

N.N.

Interior of the Kasino in Vienna during a performance of “Hamlet³”

Photograph (2005)

Courtesy of Burgtheater, Vienna

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The production was directed by Jürgen Golsch and Angela Schanelec after the play by William Shakespeare.

N.N.

Auditorium and stages for “Missa in a minor”

Mladinsko Theatre (1980)

604 x 402 pixels, digital photo

(analogous original is lost)

The archive of Mladinsko Theatre

In the production of “Missa in a minor” director Dušan Ristić claimed all the available halls in the Baraga Seminary (the present day downstairs hall at the Mladinsko Theatre) in Ljubljana for a utopian realisation of total theatre. The public was situated in the middle and the scenes were all around.

Around 1900, new architectural ideas emerged, mirroring the ongoing changes in society: the boxes were removed or reduced to a royal box, and the auditorium was designed in such a way that every spectator had a full view of the stage. After World War II, the “theatre in the round” placed the spectators around the action. Alternatively, the action took place around the spectators, seated on movable chairs.

Theatres in Munich, Germany, illustrate the changes.

Left: the National Theatre in a 1960s reconstruction, reviving the 1818 design, including the royal box.

Centre: the 1902 Prince Regent Theatre by Max Littmann; even though the design of the auditorium aimed for democratic equality, there had still to be a royal box.

Right: Littmann also designed the Artists Theatre, 1908, now lost.

Inventing small theatres where more intimate plays could be performed:

- the Intimate Theatre (Kammerspiele) in Munich, designed by Max Littmann in 1901 (below left)'

- an impromptu theatre-in-the-round in the Kasino, Vienna, 2005 (below centre)

- a 1980 production by the Mladinsko Theatre, Ljubljana, placed the action around the spectators (below right)